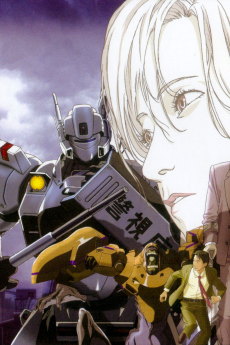

KIDOU KEISATSU PATLABOR: THE MOVIE

MOVIE

Dubbed

SOURCE

ORIGINAL

RELEASE

July 15, 1989

LENGTH

99 min

DESCRIPTION

The year is 1999 and Tokyo's Mobile Police have a new weapon in the war on crime – advanced robots called Labors are used to combat criminals who would use the new technology for illegal means. The suicide of a mysterious man on the massive Babylon Project construction site sets off a cascade of events that may signal the destruction of Tokyo.

(Source: Anime News Network)

CAST

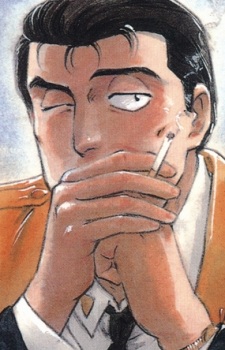

Kiichi Gotou

Ryuusuke Oobayashi

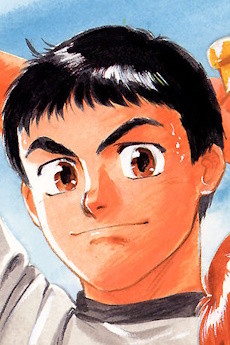

Noa Izumi

Miina Tominaga

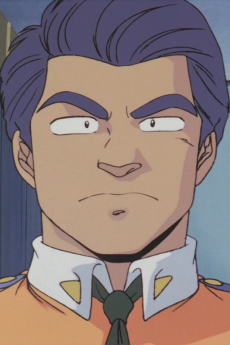

Asuma Shinohara

Toshio Furukawa

Isao Oota

Michihiro Ikemizu

Kanuka Clancy

You Inoue

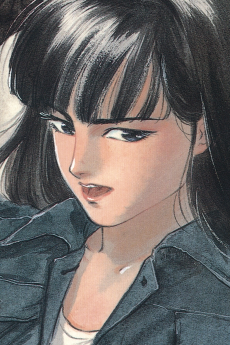

Shinobu Nagumo

Yoshiko Sakakibara

Shigeo Shiba

Shigeru Chiba

Hiromi Yamazaki

Daisuke Gouri

Mikiyasu Shinshi

Issei Futamata

Seitarou Sakaki

Osamu Saka

RELATED TO KIDOU KEISATSU PATLABOR: THE MOVIE

REVIEWS

Horipple

100/100'98 VS Type Zero: a short exchange of blows which defines a movie.Continue on AniList

„Old busted VS New hotness” is what I first said, jokingly, when this shot came up in the Patlabor movie. However, as the scene unfolded, I came to realize that my joke was much closer to the truth than I had intended.

The old against the new is one of the central themes presented in this movie, at every turn of the way we end up running into people whose lives are all too quickly overtaken by the rapid progress of technology in this world. Old engineers unable to keep up with all the new software; detectives walking streets once familiar to them, now rebuilt in sleek, modern architecture; sons rebelling against their fathers. The fast advancement of time is one that corrupts and creates disparity in all things indiscriminately, whether it be the machines raising new cities platform-by-platform in the middle of the ocean or the very food we eat.

We are made painfully aware of the detriments created when things begin moving too quickly, but just like that, with caution thrown to the wind, a path is opened up for the H.O.S. into the 8000 labors housed within Tokyo, almost all of them, with two small exceptions.

People will often say „don’t fix what isn’t broken” but if given the option to be 30% more efficient or continue as you currently are I doubt any would choose the latter.

That is Type Zero.

That cold, calculating nature; that ruthless push for efficiency; that sleek and sharp design which makes the wind whistle as it brushes against it; that sick satisfaction you get from seeing all the numbers getting bigger and bigger; that is Type Zero.

But even so, it is missing the one thing which never changes, regardless of the advancement of technology. The people.

And that, is the conflict.

That is what '98 VS Type Zero represents, even their names evoke the feeling. '98 VS Type Zero, Revolver VS Semi-automatic, Acoustic VS Electric, Rocky Balboa VS Ivan Drago.

And after their short exchange of blows that barely lasted a minute and a half, out of the two, the winner is the one with the human touch. Ei’ichi Hoba was destined to have his plan fail the moment he threw himself into the sea, letting his program serve unfailingly.

In the battle between the two labors, it is not the model AV-98 Ingram that claims victory, it's Alphonse. Alphonse with his rounded edges, all his damage and scratches, and Izumi Noa who was lovingly piloting him, and Shige who didn’t install the H.O.S. on him, Asuma the eternal backup and all the people with the SV2 who meticulously cared for and repaired him and rose up to face the challenge that day.

It might have been a short fight, but to me it is the crystallization of the movie’s themes, and its perfect ending.

DigiTheMelon

95/100Patlabor and the self-deification of the modern godContinue on AniList

Introduction

Coming from the OVA, I felt conflicted about Patlabor. Its introductory episodes were fine in their own rights, but felt disjointed as some heavily relied on comedy and the others had the perfect balance. The final three are the best examples of the latter, sporting gorgeous directing, music, and character work focused around a political narrative that wove the comedy straight into the character interactions instead of using slapstick. This perfect blend is thankfully continued in the amazing sequel to the OVA, “Patlabor: The Movie.”

Patlabor: The Movie is held together by an intense, suspenseful narrative, deep thematic values and the tools it learned from the original. It’s a movie that uses the world and characters to their fullest extent to create a mystery that doesn’t ask you to solve it, but rather understand it.

Yes, Patlabor: The Movie asks you to understand humanity and the pace of its progression when introduced to the god of the modern world.

Progression

The world of Patlabor is rapidly progressing, attempting to assert control over the literal world with Project Babylon. With this large-scale project underway to artificially dominate nature, the world demanded efficiency to match its ingenuity, giving birth to Labors–the mechas in this series. As I introduce the world in this manner, there should be a visible hierarchy. If nature and the world is being altered by machines. How do we treat someone with complete mastery over these very machines?

Before we answer that, let’s further discuss this progression. The movie excels in using imagery to display the effects of Tokyo’s rapid progression in response to Project Babylon.

From the movie’s very beginning, we’re shown a new layer of war: a concept virtually integral to humans. Alongside the human soldiers, giant mechanical combatants crash into a forest and begin firing. Their enemy: another machine, one with a distinctly inhuman shape as if showing how combat itself is progressing to the point where man deploys monsters.

Continuing this is the introduction of the Type Zero Patlabor– a sleek, cold upgrade to the Type 98. It abandons the softer look of the 98 in favor of a thinner, sharper design that Noa describes as “evil.” Complementing the physical technological upgrade is the HOS, an updated operating system proven to increase efficiency by 30% and the element most integral to the plot.

Acknowledging this progression, means we must acknowledge that it means to leave things behind. Seemingly massive stretches of Tokyo are abandoned and forgotten, brought about by the focused expansion of Babylon. Legendary mechanics are being left behind by ever-evolving technology.

While this idea exists in other characters, it’s most exemplary in the movie’s main antagonist Eiichi Hoba.

The Modern God

Eiichi Hoba is a god. In a world that relies on the Labors, the unparalleled genius with direct control over them can’t be anything else. His suicide was the moment he shed his mortal coil, and began his deification.

Hoba is a character we never directly interact with, yet his past and the actions are thoroughly explored. His motive is never really explicitly stated either, leaving the viewers to piece together their own idea of him. It’s a sort of meta-mystification of the character. Because he’s a character with no real past, having erased it himself and the only paths he left behind were a trip through a decaying city and religious metaphors, elevating his actions beyond human.

Focusing on those religious metaphors, shows us a layer of his self-perception. He considers himself god, supported by his acceptance of his nickname Jehova– the god of the Old Testament. His plan relies on the Ark and he hints at Babel. Eiichi Hoba is going to enact his judgment on humanity.

This is where you can create two Hobas: the God who propels technological progression or one who punishes it. And, it depends on how you understand the trail he left behind.

The exploration of his former homes show the direct result of progression, so for his trail to lead people to it does it mean he wants to expose man for their hubris and abandon or does he want to demonstrate how he will lead man into a new world?

Yet, the constant is that he’s someone who supposedly progressed to the next stage. Hoba’s final calling card is the 666 attached to a crow. It’s the number he’s identified with: that of the devil. Progression in his manner is an evil.

Which leads us to Noa, the preserver of the status quo.

The Extended Metaphor

There’s a very discernible irony in the fact that a character named “Noa” destroys the Ark in the middle of the typhoon. It’s a flip on the biblical story in which Noah boarded the Ark to escape God’s flood. This time, we have someone taking a stand against the punishing action of a god.

A key point of focus is that Noa both destroys the Ark and finishes off the Type Zero– the epitome of progress– through the use of her own body rather than the 98 (not to say the 98 wasn’t integral, @Horipple’s review excellently showcases the meaning of the climactic battle between the 98 and Zero).

It’s the direct human participation that is able to challenge the absent god and his empty machines. It’s the efforts of the SV 2 that protect the world we have, instead of one we could have.

Shinohara and Noa demonstrate personal growth almost in-parallel to Tokyo’s technological growth. But, they don’t need to leave anything behind. Shinohara maintains his human touch and connections while being pushed by an indomitable will. Noa trusts the Alphonse that’s supported her all this time and places her faith in Shinohara. She’s someone with deep attachment to life and the world, reusing the name “Alphonse” for the things that she loves. These are the two who stand in direct contrast to Hoba.

They’re “superheroes.”

Let’s kill god. Or, suggest that god is dead. A very nietzschean principle. SV 2 hosts the superman: those who are able to cultivate their experiences and become their own personal god. Instead of forcibly becoming the god of the modern world, the SV 2 reach their peaks as people. A group of people bonded together by their duty defeated the lone egotist.

Cautionary Tale

Understanding Hoda as god as the SV 2 as supermen helps us to understand his motives and their development to complement it. But, there’s still the risk of progress presented to us: that along the course of our evolution we’ll see that our greatest enemy is what we created.

Conclusion

Elaborating on my thoughts from the introduction, this section is more-so on the score. Patlabor: The Movie is amazing. It’s an experience that met the hype. The animation is fluid, the artstyle is charming, and the direction is cut above. Whether it’s to display the despairing emptiness of a location, the dramatic action and tension of a situation, or the emotion in a character’s conversation, the movie excels in its presentation.

What works the best is how this movie controls its tone and utilizes its cast while still being Patlabor. Because this movie is funny when it wants to be, and it's perfectly appropriate. But, it’s also strong emotionally and a serious drama. Placing the focus on select members of the cast worked in support of this, as those were the characters who could function in this type of setting. Ota, for example, shines best in comedic settings while Gotou is amazing in calmer, more subtle stories.

The narrative is tight and contemplative for the viewer, and the world is inherently interesting (if you care for the political and social nuance presented in the OVA). The villain poses questions and introduces themes that are effectively tackled and paralleled throughout the film. The characters are strong and likable. And it all comes together for a great experience.

Overall, 9.5 out of 10. Would watch it again.

ohohohohohoho

74/100Making the Possible Impossible: "Yesterday's Science Fiction is Now a Reality"Continue on AniListWith spoilers.

Real Robots

Photography, and by extension film, is the medium that embodies modernism. It is scientific, both in the process and in the precision of its rendering. It makes a mockery of the attempts of fine artists to depict scenes and figures with a sense of "realism" or "naturalism" with their paints and pencils. The likes of impressionism, and later expressionism, fauvism, cubism, and so forth, began to appear in the tradition of painting, alongside the proliferation of photography and photographic images, as counterpoints. Impressionism is directly informed by scientific discoveries about light and optics, but it used that knowledge to break down objects into patches or points of light, to transfigure movement into a still image without losing anything, to capture what's sensed but not quite seen with human eyes, nor expressed in a photograph. These new forms carried out an impulse that began with Romanticism, which was too early to be a reaction to photography, but not for the scientific rationalism of the enlightenment. How do we depict the subjective, experiential or phenomenological truth that is not captured by a scientific replication of "reality?" Not reality, but what we sense exists in excess of it, beyond its scope. The Real, or alternatively, the sublime.

Real robot is not a genre that depicts anything much like reality, obviously. Or is it obvious? Real robot is only "real," perhaps, in virtue of its contrast with the format of the super robot genre. The idea of a potential for more realism in robot anime derived from a sense, mistaken or not, that super robot is excessively false. Let's not stop there. The idea of "reality" itself, of all realisms, are generated in opposition to a belief that we are somehow only seeing fictions and semblances, not only in the worlds of super robot anime, but in Romantic paintings, gothic novels, soap operas, social media feeds, and so on.

Likewise, an object like an "organic tomato" (bear with me here) can only be conceived of in opposition to what has come to be understood as a false, inorganic tomato; some kind of monstrous science experiment of a tomato, a genetically modified organism, or something raised with pesticides and chemicals and other obscene methods beyond our naïve consumer understanding and all the more sickening. But "organic" tomatoes are still only desirable cultivars developed with agricultural methods. What does it mean to be natural, real, organic?

Headgear takes the logic of real robot even further than Tomino, its pioneer. Tomino, whose intention was not necessarily to depict "reality," but to find a setting in which to situate robot anime that could still facilitate the depiction of character driven, ideological drama. What's "real" in Gundam is not the construction and operations of the robots relative to Mazinger, to Mars, or Zambot 3. It's not even in the stylization of the characters or of their speech. The same kind of truth appears in Gundam, a real robot anime, as appears in Ideon, a super robot anime. The truth of the apparent malleability of solid objects themselves, their ability to cast different shadows of meaning depending on the position from which the gaze of the subjective viewer originates. What really is a Newtype (according to Tomino, "a type of human that could comprehend someone else without any misunderstanding")? Are they even real within the series? What kind of person is Char? Are the Zabis carrying on Deikun's legacy or bastardizing it for their own ends? What is the Giant of Id and its Id energy? What is alien about Karala?

This is what creates the apparently insurmountable challenge of proper mutual recognition between one person and another, of developing a working, totalizing ideology and ethics that excludes no one. It's why Zeta's Reccoa, who questions and eschews all recognizable ethical codes around her, is a lot like Ideon's Karala, whose ethics are grounded only by the Giant of Id, which is, in a way, a god of Karala's own invention, her secret wish realized. A god whose demands, which mirror her own, in the end even she cannot satisfy. Neither Reccoa nor Karala is properly at home with any faction, they are the radically excluded elements of the social orders.

You might say that the story of the Tower of Babel, in which humans are punished for their technological hubris, is also a myth of the very origin of this impossibility of mutual recognition:

Before this line, God says: "Look, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them." This is the origin of "impossibility," of misrecognition itself. Because God feared what humans could achieve with proper communication and an intuitive understanding of reality and each other, She engenders the downfall of communication, and consequently the efficacy of science and technology, in one fell swoop.

The sort of truth presented in an anime of Patlabor's ilk is not a matter of a truth in the sense of a scientific replication of reality, how things "really work" or "really are," but again, rather in terms of elusive meaning, in terms of the nature of experience, in terms of the amorphous problems of communication, of subject-object and intersubjective relations. It's the truth of the unfolding of this gap of "impossibility" humanity has been cursed with, as a presence in our daily lives and large social projects. On the other hand, we must admit that the level of detail, especially environmental detail, alongside the relatively reserved stylization of the characters, can only signal an intent to part with the so-called "falsity" of anime. It's the ultimate deceit. The lush detail, too much to see, and smooth, expressive animations magnetize the eye to a realism that is more real than reality.

A tidbit that always stuck with me is the notion Oshii says was behind his inclusion of the birds in Patlabor 2. The birds do not represent anything in a sense of some symbolic economy in the visual narrative. They precisely function as nonsense, noise. They are deliberately included meaninglessness, in a medium where everything that appears onscreen is typically added with intention, being hand-drawn into the frame. He even speaks of entire cuts added to his films with no purpose except to be purposeless. (Although he's specifically talking about Patlabor 2 in a book about Patlabor 2, I suspect the same applies to this film, and his others. There are even still birds in it!) Of course, they are still added "with intention," as opposed to accidentally, and we can still say that they do have meaning, apart from attempts to divine their symbolic meaning. They reveal a structural notion with regards to the form of the film and the relationships of the very images in it to the viewer. They are a wild attempt to recapture something of the realism of live film. They are a positive realization of that which is in excess of meaningful experience, that which escapes notice: the holes in our webs of impressions of the world around us as human subjects. By exposing the essential meaningless stupidity of a natural object, and our impulse to imbue it with meaning, an impulse that the mere presence of an object invites, Oshii attempts to even outdo the realism of live film by bringing in something that stands in excess of the symbolic.

The Babylon Project

Point 6. Any process that is intended to serve as a fragment of a politics of emancipation must be held superior to any managerial necessity.

To add a single brief comment on this: we have particularly to assert this superiority when the managerial constraint is declared to be 'modern', and is claimed to result from a 'necessary concern to reform the country' and 'put an end to archaic practices'. It is a question of the impossible, in other words the real, which alone lifts us out of impotence. 'Modernization', as we see every day, is the name for a strict and servile definition of the possible. These 'reforms' invariably aim at making impossible what used to be practicable (for the largest number), and making profitable (for the dominant oligarchy) what did not use to be so. As against the managerial definition of the possible, we must assert that what we are going to do, though held by the agents of this management to be impossible, is in reality, at the very point of this impossibility, no more than the creation of a possibility previously unperceived and universally valid. - Alain Badiou, Meaning of SarkozyThe Babylon Project is a reclamation of land from Tokyo Bay and the Pacific Ocean, in order to assure Tokyo's status as an "eternal city," like Babylon. The Project incites the development of Labor technology to expedite its own completion. 45% of all Labors are used for its development; but Labors are also appropriated for criminal use. Hence their adoption by Labor-wielding police to oppose those same criminals.

Meanwhile, the floating maintenance port where the Labors for the Project are housed is called the Ark. Alongside the Babylon Project, new Labors and a new operating system called the HOS (Hyper Operating System) are being pushed out by Shinohara Heavy Industries, aka SHI. HOS improves the productivity of Labors by 30% (although Noa Izumi and Asuma Shinohara agree, it's the capabilities of the pilots that really matter, for sure! And yes, Officer Asuma Shinohara is the disgruntled son of the CEO of SHI) but unfortunately, as we'll see, there's a catch...

What is the actual, historic city of Babylon? Is its identity connected with a stretch of land? The physical constructions that sit upon that land? Or is it an identity given and taken by whatever state rules over the land and those constructs? Is it a matter of the residents' belief that their land is Babylon?

In several Abrahamic religions, Babylon has become a metaphor, an imposing embodiment of moral degradation, oppression, exile, and cultural confusion. Babylon is out of accord with what's Natural and Good, but this Natural and Good is always defined with relation to the God of these particular faiths. God itself is different for each, yet the same God who feared the consequences of humans progressing too far from our "natural" state. Babylon is out of accord in the eyes of those faithful who see it, and its culture, as an obstacle to clarity and morality, a breeding ground of sin. Again, Nature here is actually defined in reaction, through a negation. Nature is what Babylon and its culture are not. Unnatural comes forth as a condemnation of what is already feared and disliked, from notions of equality and liberation to the possibilities of science and medicine, despite "nature" having nothing to do with it. Are the laws of nature possible to defy? It is in this precise way that religious fundamentalisms to this day remain a critique of the globalizing Neoliberal Capitalist regime from exactly the wrong perspective.

Babylon was decidedly not an eternal city. Its initial importance was a function of its geographic and strategic value to any empire that subsumed it. To its surviving residents, whenever Babylon changed hands or its very form, whatever was still there where they remained settled was Babylon, regardless of any outsider or ruler's recognition of the name. To travelers seeking Babylon, it could not be found, it could only be missed due to its apparent difference from its legendary glory. Yet it is immortal as a function of its mythologization, which precisely arises from its physical absence from the world. Nothing is ever "eternal" except as a legend with no proper referent. So what does Babylon have to do with this Tokyo of the future? What does the Ark have to do with Labors? What can these be but portents of Tokyo's destruction, or a wish to be destroyed and converted into legend?

If Babylon was the home of the original "Tower of Babel," it's in Tokyo that the myth is being repeated in Patlabor.

The Ark is a space designed to be inhabited by Labors, the way the Babylon Project is repurposing once water-covered land for the inhabitance of humans. If there were a great flood, not humans, but Labors would be saved. What's strange about being on the Ark is the sense that Labors are actually the ones invading the human world and making it their own, of their own accord. Shinohara likens being on the Ark to being like Gulliver, in a strange world. But that strange world is built on earth by human hands; just like the Labors are, which nonetheless seem to be developing of their own will, and their own devoted spaces. The Ark is later compared to an eerie shrine filled with idols.

Perhaps not too surprisingly, the criminal incident that the narrative hinges around is one of unmanned Labors going berserk, apparently on their own, which leads to the inspection of every labor with the new HOS system installed. This feeling that the Labors are exerting their will as they invade human society, the menacing feeling that Noa feels as she gazes at the "evil looking" Type Zero, and it seems to gaze back, becomes manifest in these incidents.

Mind you, Noa usually thinks of her own Labor, which she's named Alphonse (Alphonse the III, following her dog, Alphonse, and cat ,Alphonse II), like a cute pet, a companion. But suddenly, she fears this potential for subjectivity to spontaneously appear in the Labors.

Perhaps the Labors aren't the only human creations that we fear are out of our control with wills of their own: perhaps their very name is a metonym for the political economy. Mikiyasu complains about the demands of work interfering with his married life. The constant technological revolutions do not merely lead to the (often false, or planned) obsolescence of old technology, but also old expert engineers. The space wasted and forgotten, the lives destroyed in the wake of the collapsing real estate bubble of the 80s, we are shown evidence of. Market interests, and the plans for the rollouts of the HOS, the new Labors, and the Babylon Project, all interfere with investigating the berserk Labors. Knowledge must be disavowed in the face of impossibilities dictated by the codes of the political economy itself. If you know about something that's impossible, knowing is useless. It's not enough just "to know," the belief must also be consciously conceivable and permissible to the mind of the social order. One can know and somehow not believe, or even know and be forbidden from believing.

There's a slippage from a desperation to not believe in the possibility of sentient Labors for the sheer physical and existential threat posed by such a fantasy,

to the impossibility of the problem's existence in the eyes of the manufacturers and their political ties.

There can't be a berserk Labor if it's deemed impossible with the current technology by the manufacturers. There can't be a bug in the HOS software, or someone would've noticed it, and the problem can't be called an error if it was intentional. SHI's success and reputation is on the line. Not to mention the Babylon Project. HOS can't be wiped without the manufacturer's permission, but getting that permission is itself forbidden because of what it necessitates acknowledging first: that there's a problem with HOS.

Virtual maps and data become new ways of seeing, extensions and enhancements of subjective perception. Shinohara tracks data to link the Labor incidents to HOS and map out patterns of where they take place. It points to an impossible "why?" But these new ways of seeing only create new limits, new types of oversights and impossibilities. Hoba cannot exist because he does not appear in any records. The trigger for the Babel program is something only Labors can "sense."

What makes the Labors go berserk is not apparently a specific command in their code, but a disruption of the HOS code, heralded by the Babel quote, and triggered by Infrasound. A gap in the code like the impossibilities generated by the codes of our social world, but forced open and expanded with the repetition of the word "BABEL."

In this way, Hoba does act as an analog for God, but for the Labors. The gap that's thrust open with the HOS' encrypted viral payload somehow creates the space for a kind of spasmodic, aimless will to besiege the machines. For the Labors, this is the same separation from "nature," the same gap of misrecognition and impossibility that God beset upon humanity in light of our terrifying achievements with the Tower of Babel. A space where autonomy, where subjectivity itself invades. A disruption of the determinism of pure material reality governed by physical and biological law. A liberation from a unity with Truth. The labors are no longer mere objects, or rather, they reflect back at us the ambiguity of our own subject/objecthood.

A deadlock begets an impossibility (unreadable code), which fractally unfolds: into the realized impossibility of a living, willful Labor; and bringing to light impossible, unacknowledgeable facts, such as Hoba's existence, HOS' faultiness, the unsafety of the new Labors, the necessity to delay the Babylon Project, and worst of all, the general potential for Labors to cause harm, to invoke distrust, when they are so apparently crucial for the future development of mankind.

These impossibilities all point directly to what the problem is, but how do we solve a problem that it can't be admitted actually exists? Secretly, of course. Without even directly speaking of the plan except through ciphered language. Going through the "proper channels" incurs catastrophe and mountains of paper work. The only proper channels for solving a problem are improper ones, unknown ones, even illegal ones.

Great Chaos Under Heaven

What Hoba exposes is precisely Tokyo's wish to destroy itself for the sake of its own immortality. However, this process is to happen in the capitalist mode, the way capitalism comes back from every dead-end, crisis and recession that seemingly must kill it: the mode of perpetual self-revolution. What of Tokyo actually survives this self-revolution? Tokyo is already long gone and beyond recovery, it's just that its citizens still believe the land on which they stand to be Tokyo.

Hoba recognized many of the operative codes and their impossibilities: what data to erase, what data to preserve, the logical necessity that a company like SHI would buy HOS, push it out without hesitation. Indeed, Hoba also brings his Godlike-self into being when he commits suicide, which sets his plan irrevocably in motion. His physical absence is what makes the events unstoppable, leaves only SHI to blame, and also, what makes him seem Godlike. Perhaps it will even assure his immortality in legend.

We follow his trail of past addresses through a winding graveyard of empty bird cages. The mechanistic form of the political economy gives a deterministic sensation to the forward movement of the events as Hoba foresaw them. The plot unfolds with an uncanny air of fate, continuing without his oversight, that pairs with the Biblical register of Hoba's persona in coincidence with Tokyo's own Biblically named constructions, and the arrival of the typhoon. We are wrapped up into Hoba's delusion that he is God. However, it's his own scientific hubris that foils him by leading Gotoh, Shinohara and co. to seeing what should have been impossible to see.

The fatal, Biblical quality of the plot nevertheless makes it unbelievable to their higher ups now. That, in addition to the fact that it's no less unthinkable to stall or jeopardize the Babylon Project, or to confront their own complicity with creating this problem, or the inadequacy of their codes to recognize or talk about it without ruining everything. The only thing that is allowed to destroy the Ark is, as Gotoh suggests, "an act of God."

Patlabor 2 exposes the global violence that sustains a climate of Liberal Democratic peace domestically. This film exposes the waste that is created by the perpetually self-revolutionizing market, as well as the exploitable, manipulatable logic of the market (is this not the very work of the finance sector?) and the bureaucratic systems that manage it all. But are we not giving too much credence to the critiques of a fundamentalist here in Hoba? Or, despite the religious fervor and flair, is it actually not Hoba, but the Mobile Police who are too conservative in their answers to the capitalist logic? Are we simply to grow our own tomatoes, and skeptically refuse to upgrade our OS? Does this really make them "superheroes" as detective Matsui says? Are they thus outside of the system, or a danger to it? Let us not forget that ultimately, their job is its preservation. Perhaps the most fruitful question is, what sort of God is participating in this "act of God" that Gotoh suggests is the answer to their predicament, and how, if at all, can this God help us?

While Hoba fills the place of God in his own plan, Gotoh rather intends to use the name of God as a cover up. He will dismantle the Ark, but say it was an unpredictable act of nature. It's only in this way that we can save the people of Tokyo, interrupt the Babylon Project, and not embarrass or blame any of the professionals or politicians who are actually responsible for the mess. "Through God all things are possible," even the impossible.

Without actually counting on or believing in God, or even Nature, such an entity is invoked as an excuse, revived in order to permit an unacceptable act: to put the safety of the people before the interests of the economy; to admit that something happened that the systems of science and government we put faith in neither saw coming nor could protect us against, not strictly due to a lack of vigilance, but because of built-in shortcomings. If no one is authorized to permit it, then we can give ourselves permission, only in God's name. God does what God has always done best here: fill in the blanks where the answers are not provided. It's not the God of a transcendental morality, it's the God that offers an explanation where there is none. Where the state and science leave gaps, where we sense the excess beyond social reality, we have mysticism to take over. But this mysticism is now apparently not genuine. The answers were found out, known to some, but simply unbelievable, unacceptable; not because the answers were genuine impossibilities, events defying the laws of nature, but because they defied our faith in the pillars of society, or the very parameters of our subjectivity. It's not easy for the authorities, nor for us to believe that Hoba could achieve what he did, or even perhaps that he truly existed. Meanwhile, the Babylon Project and the Ark betray whose side the Tokyoites believe God is on, who is God's chosen people.

It's not that Gotoh's act is ethical because he believes God is in support of it, or that it's in line with a specific religious ethic he subscribes to. Rather, the only way to act in the way he believes to be ethical, and to get away with it, to do it without violating the social codes, without utterly sacrificing the economy and important peoples' reputations, is to blame the results of his operation, the destruction of the Ark, on a God that he knows won't intervene. Actually, the typhoon is on Hoba's side, if anything. Gotoh acts against God, or at least in spite of God's inaction, and makes God his scapegoat.

That all said, doesn't the story remain creepy to the end? Is mysticism really dispelled? It almost seems that Hoba's impossible scheme is even more impossible to prevent, leaving us wondering to the last if the heroes will actually pull off their counter operation. The idea of the Labors turning themselves on and lashing out never fails to inspire fear, and questions of what the HOS is even doing to them, or if there isn't something frightening already in them that it's merely brought forward. Isn't there something of a dark intelligence apparently lingering in the eye of the Type Zero? Doesn't everyone, characters and viewer alike, believe for at least a moment that it could really be some kind of ghostly or undead Hoba on top of the Ark (perhaps, though, the inscrutable birds are even more disturbing)? Carrying out the apparently impossible really seems to open up all of these supernatural possibilities, at least fleetingly. That's the feeling to latch onto, here.

Why do we experience the machinations of our own brains and sensory organs as "consciousness?" Why is a part of nature experiencing itself? Is it not precisely a result of this gap of misrecognition and impossibility? Self awareness is actually a kind of self-unawareness, an inability to really understand or accept who and what we are, what we want, why we're here. What am I to other people? Apparently, this is thanks to God muddling our language. God rent us from "nature." It's God who put Eve in Eden with the fruit of the tree of knowledge and said "don't eat it!" in effect granting humanity both autonomy and sin. How can we claim morality to be a return to a more proper accord with nature while referring to God as an authority on the matter? Freedom arises in those moments a close confrontation with an impossibility, a prohibition generated within the code, causes the code to undermine itself and break down for us in self-contradiction. Not merely through our transgressing against the code and doing the impossible does this happen; nor through an erasure of all impossibilities; but through a total reframing of the necessities and impossibilities the code dictates. Without misrecognition, there is no subject, and without impossibility, there is no freedom.

I prefer to think that Noa leaves Alphonse in her final confrontation, not to deal with the situation specifically with her still-dependable, "natural" human body, per se, but rather to reassert her occasional, minimal freedom from the rule of the codes altogether. To step away from her beloved Alphonse is to step away from the code itself. The Type Zero is driven like a zombie by its corrupted operating system, which survives being wiped, overwritten, even one or two buck shots. What she contends with, both physically and in terms of her own fears, is not the existence of the Type Zero itself anymore, but purely the immutability of the operating system, running its repetitive operations to infinity on the fuel of its own inexhaustible, zombified drive.

What is disturbing about the zombie Labors is the outward resemblance of their "mental" innerworkings to actual human subjectivity. It's horrifying to see them lined up on the Ark near the end, their cockpits illuminating as they start to move with no pilots inside them. No soul, only hardware and code, "and yet it moves." Seemingly even with clear intention. This unaccountable void that seems to somehow presage or bely consciousness is what Noa really sees in the eye of the Type Zero. Yet I also want to recall again the metonymic relationship of the Labors with the political economy, which also seems to have a logic and a will of its own that we must obey.

A human being does not need to wait for someone to change its operating system. Indeed, Noa upgrades hers in that exact moment she's facing the Type Zero, eschewing the laws and boundaries, just as she commits the film's final impossible act, and its most desperate and beautiful. Alphonse cannot possibly defeat the Type Zero. So Noa is told again and again in that scene, by Kanuka and Shinohara. But she has to stop it, and she has to save Kanuka. She has feared the Type Zero and its gaze since the beginning of the film. It's not an embrace of the physical or natural or a rejection of the cultural or the technical. Rather than being symbolic on that sort of level, it's that she takes this confrontation with the impossible as an opportunity to totally reframe, to act absolutely beyond the code, beyond the operating system that governs the world of the film; and this, without blaming it on God. It's not a simple rollback of one driver to an older version that's needed, it's not a greenhouse full of organic tomatoes, it's not mourning the ruins and the waste and the abandoned bird cages. It's this realization, which is itself made impossible to us, a realization of a fact we know, but nonetheless cannot believe: of our ability to radically alter the code of the political economy and survive.

SIMILAR ANIMES YOU MAY LIKE

OVA ActionMacross Plus

OVA ActionMacross Plus ANIME AdventureTetsujin 28-gou (2004)

ANIME AdventureTetsujin 28-gou (2004) ANIME ActionPSYCHO-PASS

ANIME ActionPSYCHO-PASS ANIME ActionSilent Mobius

ANIME ActionSilent Mobius

SCORE

- (3.75/5)

TRAILER

MORE INFO

Ended inJuly 15, 1989

Main Studio Production I.G

Favorited by 317 Users