KANASHIMI NO BELLADONNA

MOVIE

Dubbed

SOURCE

OTHER

RELEASE

June 30, 1973

LENGTH

89 min

DESCRIPTION

The beautiful peasant woman Jeanne is raped by a demonic overlord on her wedding night. Spurned by her husband, she has no outlet for her awakened libido, which develops to give her powers of witchcraft.

The film is inspired by Jules Michelet's non-fiction book "Satanism and Witchcraft", it is the third and final film in the Animerama trilogy, and the only one to be neither written nor directed by Osamu Tezuka.

(Sources: ANN, Wikipedia)

CAST

Jeanne

Aiko Nagayama

Jean

Takao Itou

Akuma

Tatsuya Nakadai

Okugata

Shigaku Shimegi

Ryoushu

Masaya Takahashi

Shisai

Masakane Yonekura

Piero

Taisaku Akino

Narrator

Chinatsu Nakayama

RELATED TO KANASHIMI NO BELLADONNA

REVIEWS

Peng

90/100A free fall, a reverie, a fever dream in the guise of watercolour hentaiContinue on AniList“To be convicted, a witch usually had to be brought to confess. But the signs of witchcraft could also be found on the witch’s body. These signs were the province of the executioner. In Würzburg, the mere threat that the executioner would shave the witch’s body and investigate any apparent marks was often enough to precipitate a confession … There was clearly a sexual element as well, for diabolic marks were often found around the genital area."

"It was believed that the demon could secrete himself in the folds of a witch’s clothing, enabling her to withstand the interrogators or even do them harm. She had, therefore, to be undressed.”

- Lyndal Roper, _Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany_ (2004), 54. The body is central in the medieval and early modern mythos surrounding witchcraft. Given how prominently the body features in Catholic tradition - the Eucharist, for example - this is unsurprising. But when it comes to witches, the body was ground zero for everything concerning the diabolic. Accuse her of fornicating with the devil, strip her, shave her, misidentify a birthmark or two, hook her up to the strappado, stick some needles into her, burn her at the stake, and scatter her ashes under the gallows as added insult. Naturally then, the body - specifically the naked body - is centrepiece in _Belladonna of Sadness_. As the final entry in [Osamu Tezuka](https://anilist.co/staff/96938/Osamu-Tezuka)’s _Animerama_ hentai anthology series, of course it would be. However, whilst _Belladonna_’s lurid imagery is undeniably erotic, sometimes hilariously so, it’s rarely titillating. And if it’s aim is to arouse (it isn’t), then it does a pretty shitty job. But that’s not why you’re thinking about watching it.

But there is a story. _Belladonna_ is loosely based on Jules Michelet’s [_La Sorcière_](https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25417539-la-sorci-re?from_search=true). Michelet forwards a sympathetic view towards witches here, framing the sabbath as a form of popular rebellion against feudal power structures. _Belladonna_ is about rebellion too. Through Jeanne’s degradation we witness her subjugation. Through her transformation she becomes a saviour, leading the (willing) people to blissful damnation. And through her ultimate fate, Jeanne realises apotheosis. Throughout this, _Belladonna_ both embraces and rejects the body. It embraces it, as we’ve detailed, aesthetically. For after all, as the kaleidoscopic orgies are testament to, the body is beautiful and grotesque. On the other hand, it rejects the Church’s doctrine of the body as propaganda and the woman as sacrilegious. Rather, the body is a commodity. Not one that belongs to God, local lords, or husbands, destined to be used and discarded, mind you. But one belonging solely to Jeanne. A bargaining chip that assures her empowerment. Just as the phallic devil and his crossroads deals are too. What’s really important is what happens after the fact. Through Jeanne's sexual liberation, she finds not perdition, but enlightenment. _Belladonna_ isn’t about humanity’s decadent decline. It’s about its salvation. Should _Belladonna_ be avoided by epileptics? Probably. Are its efforts to frame Jeanne’s experience as universal sometimes clunky and forced? Yeah, a little. Is its story one of unparalleled ingenuity and philosophical insight? Not quite. But what it executes well, it executes with hypnotic style. _Belladonna_ is not quite garish enough to be the ultimate midnight movie material. Nor is it impenetrable to the same degree as more obscure arthouse titles. And am I reading a little too much into it all? Possibly. But that’s where half the fun lies.

Fleur

85/100Experiencing Belladonna is very much like falling down a bottomless rabbit hole.Continue on AniListA corrupted woman is soaked in sin and gradually torn from her soul. Her purity that was once unscathed is now an unbounded commodity. Piece by piece, she is dismantled until the only thing that’s left is flesh and blood. From the ashes of unadulterated youth, now rises something else. The transformation from beauty to grotesque is immediate. A woman is either a maiden or a witch. A sin or a sinner. An unknowing victim or an unholy perpetrator. The existence of both is morally reprehensible. Here we have the scripture of ye old storytelling embedded in every culture, every time, and in every form.

Nonetheless every artifice, every duality inherits a line that exists to challenge it. A tempo-spatial blip where white melds into the black – where Angels mingle with Demons, where grotesqueness is beauty, where tragedy births empowerment, where witches ARE women – explodes with a forgotten force. That coalescing blip takes form in Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi no Belladonna): a powerful visual enigma that mesmerizes with bizarre aestheticism and erotic storytelling (one that many will probably write off as a “deep” hentai and in the process, dismiss the work so passionately fueled by the revolutionary spirit that drives all provocative art).

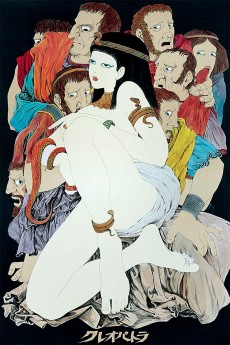

Belladonna is the third and final installment in the Animerama series (adult-themed films) conceptualized by Osamu Tezuka, but due to his early abandonment of the project, it was sought through (in 1973) by Eiichi Yamamoto and produced by Mushi Production. Adapted loosely from the non-fictional musings in La Sorcière by Jules Michelet, Belladonna follows the vicious downfall of a young girl named Jeanne, and thus, her metamorphosis. Even though Belladonna takes influence from Michelet’s book, it is not a literal re-telling. The novelty of Michelet’s work, however, should be noted. La Sorciere attempted to trace the rebellions against feudalism and Medieval practices that subjugated women and peasants. Riddled with folklore, fairy tales, and religious theory, the book opened a new sympathetic vision towards the oppressed, and what eventually manifested into “witchcraft”. Belladonna is a tale about oppression, but also about revolution. What starts off as a fatalistic chain of events steeped in sexual violence and tradition, morphs into a darkly, disturbing tale of empowerment (featuring Satan symbolized as an ever-growing penis, lots and lots of other phallic imagery, and intense psychedelics visuals).

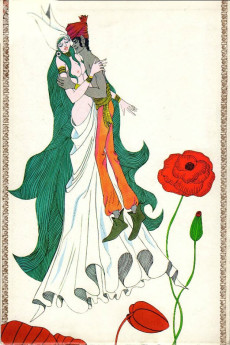

The aesthetical direction in Belladonna is unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Sequences of stylistically-independent paintings that are tied by motion. Styles include Klimt-influenced artworks where the female body is the everlasting focus. The only place where precision in detail matters is on Jeanne, and partly her husband and abusers. Following in the symbolist tradition, many embodied the elements of Decadence. These paintings were full of lurid, exploitative objects that were flourishing with mystical context. Decadent art called for transgression and taboo and expressed them through dreamlike visual poetics. Belladonna adapts this with acuity. Abstract, expressionistic paintings also take hold here. The use of placement, distance, object and how they come alive, both with color and shape all reveal this. There are scenes that are built entirely on geometric progression. The painting starts at one point, transforming into a set of shapes that blooms into the eventual scenery. Kaleidoscopic backgrounds and mural-stoned-faces swell up the screen, while continuous mutations and distortions keep the atmosphere full of psychedelic vigor. It’s like a never-ending party in the 60s. The art-style is intensely experimental and frequently disorienting. The styles and influences here are endless: watercolor paintings, ink-stencil portraits, sketchbook graphics, bubbly cartoons, and the list goes on – of all the various art-styles contained in this film. Even though the film ranges in the kind of techniques it employs – many of them being direct contrasts to one another – it never hiccups, not even once. The continual change in style becomes equally as important for the story. It’s a story with centuries of sociopolitical turmoil, unveiled through centuries of art evolution on canvas. And the best part is that it’s always fluid and always flowing.

Consequently, Belladonna's art is demanding, bold, highly erotic, often-etched-imminently, and absolutely unforgiving. The shots move ever-so emphatically; scenes feel as if being drawn out right then and there. The horror here transposes itself not just as a genre, but a state, an endless feeling that seduces the senses while suffocating the mind. There are scenes comprised of simple shapes, lines intersecting, and splashes of unending red and black that are more horrific than most horror films attempting to be anything more than a gore-fest nowadays. The film functions in directional panning waves that slide from painting to painting, with minimal movement and sparse dialogue. One of the most laudable aspects was the use of motion. Films, at a very fundamental level, need to master the skill of motion; to be able to capture the mobility of ideas in a visual format. In the same way that sometimes silence speaks louder than sound, stasis expresses visual ideas more potently than systematic movement. It’s animation revised: unbridled by traditional sequential movement, materialized through motion on canvas. Stasis then becomes as important as motion. Belladonna proves this with its delicate and deliberate staging and execution.

Now really, what is Belladonna about? The aesthetics tell it all. The “how” is infinitely more valuable than the “what”. Even then, there is still plenty to bask in, narratively. Belladonna is a purely visual experience, but isolating the narrative is worthwhile. Reconnecting with the earlier synopsis, Belladonna tells the seemingly unfortunate tale of Jeanne. On her wedding night, as custom dictates, Jeanne and her husband Jean must receive the okay from the baron (through paying ridiculous monetary “gifts”). As they cannot meet the high demands set by the Baron, Jeanne is subjected to ritualistic rape by the Baron and his house of ghastly courtiers. From then onward, Jeanne continues to suffer at the hands of her time, repeatedly violated by those in power and by circumstance, she finds herself in an old-fashioned predicament: compromising her humanity. It’s not original in its premise. Tales of religious persecution, power, and transformation almost always follow a similar formula: striking a deal with the devil. Therefore, the story unfolds on a two-fold: first, on the degradation of humanity and second, on the revival of it.

What sets Belladonna apart is its perspective and thematic subversion. The apparent importance of religion, tradition, and all these concepts that arise from scripture of society all take a backseat for Jeanne’s place in the world. She becomes the singular point of relevance amongst cosmic indifference, where she comes before the judgments of the world. This is crucial for the second half of the story and the ultimate, conclusion. The perspective here is refreshing, in the ways many modern fairy tales are, especially those with a female focus. The one that immediately comes to mind is a collection of short stories by Angela Carter titled The Bloody Chamber. These tales are of the revolutionaries — the nontraditional, and those unaligned with the religious depiction of “woman”–, where through the crevices of preordained evil and sacrilegious, arises positivity in the form of empowerment and transformation. These are far more important than redemption or “survival”. It’s history, art, and humanity revisited but with the scales tipping the other way. Thus, the devil becomes a tool. Evil becomes a means to an end. The deal becomes a means to an end. The body is shown to be purely material and the spirit/soul as mere propaganda. Things that held the greatest amounts of meaning become empty remnants in the face of ultimate transformation. The most important point is that woman and witch remain synonymous. This isn’t a movement to destroy humanity, but to revolutionize it.

Jeanne makes the deal and becomes a witch. Yet, she doesn’t seek revenge in the old-testament sort of horrific way. She sets the way for the townspeople and all those that violated her to find hell in their own manner, whether it’s through hedonism, paganism, or partaking in 24/7 orgies. The Black Plague is also a thing, here (and the origins are hilarious but terrifying). Jeanne helps those struck by the plague (using various plants and concoctions) and becomes their savior. With her “help”, the villagers willingly walk on their personalized road to perdition. (Belladonna is a nightshade plant. The root was used to make medicine, but the leaves and berries are deadly. It’s named after Venetian ladies who used it to dilate pupils for striking appearances). Jeanne assumes her rightly place as the Belladonna who in the wrong doses, proves to be lethal and insurmountable. As Angela Carter reformulates the heroine/woman in modern fairy tales, “Like the wild beasts, she lives without a future. She inhabits only the present tense, a fugue of the continuous, a world of sensual immediacy as without hope as it is without despair,” we find ourselves seeing Jeanne reflected in the very same words. Jeanne descends into –what we perceive as– madness, a form of clinical hysteria from any angle. Despite that, there is something far deeper settling in her reverie: “The girl burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody’s meat.” And that very Carter-ian depiction becomes the absolute state of Jeanne.

Even with the inevitable “end” of Jeanne, the story holds true to what actualized empowerment entails: continuation. It doesn’t end with the body.

Experiencing Belladonna is very much like falling down a bottomless rabbit hole. A visceral drop where one experiences each grain of the twisted earth, swallowing wholly, their entire state of being. The dive isn’t measured. It’s freefall so fast, one almost feels like they are suspended in air, motionless. During those moments, every sensory receptor is attuned to an unknown, unearthly frequency. It’s a film designed to enthrall the senses and heighten all temporality. The kind of thing people do drugs for. Spectacularly, it achieves this for every second of its runtime. Enter this with an open mind. Belladonna knows for she is woman and witch, and both exist here simultaneously.

SIMILAR ANIMES YOU MAY LIKE

ONA ActionDEVILMAN crybaby

ONA ActionDEVILMAN crybaby MOVIE Fantasy1001 Nights

MOVIE Fantasy1001 Nights OVA DramaTenshi no Tamago

OVA DramaTenshi no Tamago OVA ComedyNekojiru-sou

OVA ComedyNekojiru-sou MOVIE DramaKaijuu no Kodomo

MOVIE DramaKaijuu no Kodomo

SCORE

- (3.5/5)

TRAILER

MORE INFO

Ended inJune 30, 1973

Main Studio Mushi Production

Favorited by 690 Users