YORU NO KURAGE WA OYOGENAI

STATUS

COMPLETE

EPISODES

12

RELEASE

June 23, 2024

LENGTH

24 min

DESCRIPTION

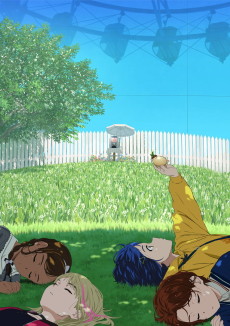

"I want to find what I enjoy."

Shibuya is a city full of identity. It is here on Shibuya’s late night streets that illustrator Mahiru Kozuki, former idol Kano Yamanouchi, Vtuber Kiui Watase and composer Mei Kim Anouk Takanashi — four young women who are slightly outside the world — join together and form an anonymous artist group called JELEE. “I” also want to shine like someone else. If it's not me but “we” then we might be able to shine.

(Source: Crunchyroll News, HIDIVE, edited)

CAST

Kiui Watase

Miyu Tomita

Kano Yamanouchi

Rie Takahashi

Mahiru Kouzuki

Miku Itou

Mei Takanashi

Miyuri Shimabukuro

Miiko

Sumire Uesaka

Koharu

Asami Seto

Melo Setou

Miho Okasaki

Ariel

Nao Touyama

Kaho Kouzuki

Ayu Matsuura

Mion Hayakawa

Chika Anzai

Honami

Hekiru Shiina

Chiepi

Hikaru Akao

Emi

Natsumi Kawaida

Yukine Hayakawa

Yuuko Kaida

Momoko Yanagi

Yukina Shutou

Akari Suzumura

Sally Amaki

Saori

Yuki Tanaka

DJ Police

Takeru Yagi

Kouchou-sensei

Hitomi Shogawa

Tatekita-sei

Mashiro Nonomura

Bangumi Shikai

Masaomi Yamahashi

Suizokukan no Oji-san

Kazuyuki Okitsu

Sensei

Yuuki Hoshi

Tatekita-sei

Miu Miyake

Oogosho Geinoujin

Kousuke Echigoya

EPISODES

Dubbed

Not available on crunchyroll

RELATED TO YORU NO KURAGE WA OYOGENAI

MANGA Slice of LifeYoru no Kurage wa Oyogenai

MANGA Slice of LifeYoru no Kurage wa OyogenaiREVIEWS

Scheveningen

80/100A strong character drama with a packed plot that hinges on a connection with its characters to sell its intense scenesContinue on AniListJellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night is a strong character drama that hinges on a connection with its characters to sell its many emotionally intense scenes. The show is very much anchored by the charisma of its cast, using it to tie together a rather wide range of themes and subjects it wants to tackle. While a majority of the narrative is focused on the specific topic of amateur online content creation, specifically in music, Jellyfish also covers wider issues with the professional entertainment industry as well as the private struggles of its characters. This does benefit the show by preventing its identity from solely being about its subject matter of internet content creation, avoiding the risk of becoming too technical or granular to appeal to a wider audience. However, it also contributes to the pacing feeling quite rapid at times with its many different themes and plot threads that are all made to intersect through the characters. The show ends up lacking the time to fully dig into so many of these topics given their gravity. Despite that, it never feels like it is pulling its punches either with what it does choose to show of the cruel and even dangerous world of entertainment and internet culture. It is an understandable compromise since these issues are natural extensions of the show’s premise yet also cannot be taken to their full “realistic” extremes without radically morphing the tone and trajectory of the show into something dour or even horrific. This still puts a noticeable strain on the narrative with how it struggles at times to both satisfy the intensity of the plot yet maintain its more hopeful and light-hearted premise without slipping into melodrama or creating tonal whiplash. But despite this tension in its narrative aims, Jellyfish still ultimately succeeds on the back of its charismatic and earnest characters, though never quite rising to its full potential with how it clearly intends to cover its themes.

The key to the success of Jellyfish has been the strong characterisation of its core cast that balances being larger than life with believability. All media, even those with a mundane setting, are to a degree a heightened reality where everything is presented in a more stylized manner to make for a compelling narrative. However, this exaggerated and romanticised veneer creates the constant risk of characters feeling too unbelievable in their mannerisms or responses to events given their supposed ages or backgrounds. The show tows this line well with the core cast portrayed both as charming and quirky enough to be engaging while being self-aware of how peculiar or emotionally consumed their behaviour can at times make them appear. With how many dramatic moments are packed into the season, the self-awareness of both the characters and the narrative is key in maintaining suspension of disbelief while avoiding a slide into melodrama. It preserves the characters' many outbursts and tears as their genuine emotional reaction to events and prevents them from feeling like they were written in for the sake of entertaining the audience. At the same time, the characters later reflecting on events having simmered down or scummed to embarrassment not only makes it feel even more sincere but signals that the narrative does not perceive these dramatic moments as ordinary nor without exceptional cause or consequence. All this serves to create characters that are larger than life but still feel bound to it and respond like genuine people to things around them. This self-awareness is also leveraged to smooth out the transition between light-hearted and more dramatic moments, even heightening the impact or catharsis of scenes with how they contrast each other in quick succession. While it is arguable how effective this is in the eyes of some viewers who still feel a degree of whiplash, it still undoubtedly helps alleviate the pressure on the suspension of disbelief by consistently framing the cast as the impulsive and mildly frivolous teenagers they are.

This self-awareness of how strange or intense the characters can appear also ties in strongly to Jellyfish’s themes of them feeling isolated or rejected by society in various ways. It serves to reinforce and show the audience that what makes them compelling characters is also acknowledged within the narrative as exactly what makes them feel alienated or even rejected by many of their peers. While a lot of their personality is still favourably framed as quirky and endearing, it is also a subtle reminder that some of these mannerisms would be a bit hard to embrace if confronted with them in real life. This framing is made stronger by the show choosing to introduce each character to the narrative in tandem with the core parts of their backstories. It allows the viewer to immediately connect their past with the character’s current views of the world and social circumstances in a direct yet subtle manner. More importantly, having all the pieces on the board from the onset is what gives the show a solid foundation for a compelling character narrative. It ensures that all the growth and obstacles throughout each character arc do not feel like they come from nowhere, all of them being clearly set up in their backstories or natural extensions from them. Even characters like Kiui who start with more unknowns about their circumstances have the incongruence between what is said and what is shown clearly telegraphed to the audience with the answers being readily inferable from the information provided. It even leverages small things that most anime take for granted as just part of character design like the unusual dyed colour of their hair to imply things about their social situation. In this, Jellyfish demonstrates it is also capable of a surprising amount of subtlety or implicit storytelling despite the general impression it makes of being a fairly direct narrative. While all this has placed the weight of making the show engaging solely on its execution and character portrayals, it is a confidence well-founded for Jellyfish. Furthermore, it resists the urge to use mystery as a crutch or narrative sleight to prop up the drama like so many other shows tend to do these days.

With all character arcs and their direction firmly laid out by episode four, it does become apparent that the show has a significant number of themes it wants to cover. They range from the struggles of a creative in finding confidence or a purpose to their work to more personal questions about self-acceptance despite finding it hard to fit in, and even rather expansive societal topics like the fickleness and cruelty of internet culture and the underhanded nature of the entertainment industry. Although these all certainly relate and overlap with each other, it is apt to question if this is too much for a single narrative running twelve episodes to cover. To tie everything together into a plot, the narrative gives more screentime to the creative challenges the characters face as JELEE since it interacts more directly with the plot threads to do with internet culture and the entertainment industry. Part of the issue with that is although Mahiru and Kano have personal struggles that relate directly to their creative work as part of JELEE, Kiui and Mei face challenges that have more to do with how they feel as individuals. Most of the events surrounding the successes and mishaps with JELEE only interact with Kiui and Mei’s character arcs as catalysts instead of being more directly or thematically related. As a result, much of the cast's more personal arcs like struggling with what they want to do after high school or why they feel rejected by their other peers end up underserved by the plot. This is particularly the case for Mei who fades into the background in the show’s middle and feels particularly static given she does not have an obvious character arc. Even Kiui’s compelling personal struggles feel more like they run parallel to the main thrust of the narrative surrounding JELEE, lacking the full time to breathe and elaboration that would really draw out all its potential. There could have been ample room to focus on the more personal stories of the characters in a variation of Jellyfish where the narrative omitted or minimized its plot threads to do with the professional entertainment industry, but that is simply not the direction they wanted to go in. While what we do get of their personal struggles is certainly impactful, it does not get the time to be explored or to breathe that would bring out its full narrative potential.

This is not to say that Jellyfish’s plot or commentary about the idol industry is without merit. It is mostly direct in showing an extremely nasty and unglamourised side of the industry while still having a subtler touch with some scenes that at first glance appeared to be played for laughs. For instance, despite the upbeat and zany framing the show frequently uses for Miiko the idol, there is always this foreboding or sinister undertone when the show reveals more about her situation in life. Yet it still feels like it has at least slightly overloaded the show’s pacing and framing with how much time needs to be dedicated to it and the effort it takes to meld the tone of such a hefty subject matter with the rest of the show. This problem arguably exists with the plot and themes directly surrounding JELEE as well since it goes into the dangers of seeking fame on the internet such as being doxed. It is a natural extension of any narrative dealing with online creation, especially with how it establishes JELEE as an anonymous group and with some of the cast having plenty of baggage tied to their real identities. Admittedly, the show cannot reasonably delve into the full extent of the scenario since it would ultimately warp the show’s entire premise around it by necessity. Not only would it require most if not all of the show’s remaining run time to get into the consequences of being doxed like harassment and the mental toll it would take, but it would also drastically alter the show’s premise from being about being an internet creative to the dangers of the internet. This kind of grim, almost horrific exploration of the topic would be more suited to a show in the vein of Perfect Blue, and at the very least would feel like a bait and switch to the audience since nothing about Jellyfish promised or even hinted at that kind of tonal shift. Perhaps there is a way to convincingly blend both a fun and quirky tone while dealing with the full escalation of doxing, but that would be an exceptional feat instead of something reasonable to expect. That only leaves the show with one option, both narratively and tonally, in having its characters respond by pushing through all the vicious comments and ridicule and forging ahead with their goals. There does still feel like a lack of time to let the gravity of the situation settle in, either by showing more of the characters processing what is happening to them or a less indignant response like emotionally shutting down for a while. But that limitation is due more to how packed the narrative is with its runtime being dedicated more to furthering other conflicts. Despite the difficult competing demands, the show still does show a significant amount of anguish from its characters to drive home the magnitude of events while not making it too dark and creating an irrecoverable amount of tonal whiplash. While imperfect, it strikes a reasonable compromise in ensuring that the characters nor the narrative ever seem to be taking it lightly while also maintaining the initial tone and vision of the show.

With the tightly packed plot and weighty topics it wants to tackle, it leaves Jellyfish relying on a connection with its characters to maintain the suspension of disbelief as the intensity of the drama. Opening the show with all the members of JELEE already being experienced creatives is certainly an excellent choice to support the stakes the show rises to. It allows the plot to essentially bypass the beginner phase of attempting to learn their craft, both saving narrative time and providing them with baggage that the plot can immediately tackle. Mahiru’s arc in this is fairly conventional when telling the story revolving around a character dedicated to any sort of craft. Despite it having the usual plot beats about lacking confidence in her abilities and how she might be going too far in the name of getting her big break, it is executed well by the show and avoids some of the common pitfalls of the character archetype. The show never makes the mistake of having a single uplifting speech from another character solve all of Mahiru’s worries permanently. Her anxiety lingers on and is never fully assuaged by compliments or reassurances despite them still being helpful. It is never shown to be something easy to get over and requires Mahiru herself to work for it throughout the show. On the other hand, Mei’s character arc is harder to see with her character feeling static for much of the season despite eventually having some major dramatic moments where she is the focus. There are some implicit ideas about her journey being one of connecting with Kano as the person she really is instead of being stuck in a parasocial relationship with the image of who she used to be. It is possible to argue the lack of emphasis on this as subtlety, but the viewer simply sees too little of how Mei’s interactions with Kano change over the series. A majority of her scenes are frequently used as punchlines or to further the plot instead of her characterisation. While she is still a charming character, it feels somewhat disappointing for there never to be a moment where Mei gets to connect with Kano and solidify this as being her character arc.

In contrast, Kano’s arc has the most consistent amount of narrative focus with her being the focal point for much of the drama surrounding JELEE given her colourful past. Yet her journey of learning to perform and create more for herself and those who care about her feels like it would be more at home in a show dedicated to commenting on idol culture. What Jellyfish delivers hits all the major plot points surrounding that, but they feel abbreviated or packed a little too close together because of the many other themes it needs to tackle. There is some interesting interaction with how Kano’s background as a former, and arguably disillusioned professional contrasts that of Mahiru’s as someone aspiring to go pro and be recognised for her abilities. Yet they still feel a little smothered and under pressure from how packed and dramatic the rest of the narrative is. Notably, a lot of the themes and plot threads relating to Kano’s relationship with her mother and past life as an idol feel like they lack the time to breathe and are a little rushed to a resolution. This pressure is more keenly felt in Kiui’s arc where it is exceedingly strong but also feels distinctly like a tangent to the main story. Despite the narrative being unable to consistently dedicate focus to it, Kiui’s character remains compelling since her personality has the benefit of having obvious layers to it. In constantly striving to project this image of confidence, the viewer always has plenty to consider with how much of Kiui’s confidence is a deliberate ruse, how much is genuine, or more complex permutations like her pretending having gone on for so long that it has become real or at least reflexively baked into her personality. Still, the potential of Kiui’s arc feels less realised than it could be simply because there is not as much build-up or time to breathe as there would be in a show more dedicated to exploring those kinds of themes. The juncture where Jellyfish leaves Kiui’s arc is still satisfying in being a cathartic moment where years of her frustrations and fears have been released. Yet it also feels more like the beginning of the end instead with how the reflection and falling action to do with her arc have been shortened. Despite the packed narrative, Jellyfish still does an excellent job with its characters, making these limitations feel more like strained or missed potential than anything incomplete. The drama is still compelling enough even in its compressed form that it is reasonable to argue only an increase in the sheer amount of episode count would improve it, and that is not something that can really be held against a show given current industry norms and expectations.

Overall, Jellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night is a show that has plenty of charm and lots of ideas. It is certainly compelling as a show that aims to encapsulate and blend the most prominent themes and stories that can be told in the entertainment industry into a single show. By far, it feels more limited by its episode count and format than any decision to be made within the narrative itself. Part of that necessarily opens it up to being a little hit or miss with certain viewers given the packed run time creates a constant flow of dramatic moments that might overwhelm them. Especially since this might reasonably veer into the territory of melodrama if for a viewer less sold or moved by the intense emotions of the cast. Nevertheless, with how earnest Jellyfish is about its themes and how charismatic it is with its characterisation, it deserves a solid 8 out of 10. It is tempting to give it an 8.5 or even a 9 with how compelling I found Kiui’s character in particular. But the compression of everything in the plot makes it seem distinctly like the show is biting off more than it can chew despite it never feeling like melodrama to me. Still, it is not unreasonable for some viewers to give it a higher score or perhaps even have Jellyfish be one of their new all-time favourites due to how compelling they found the characters to be.

Mcsuper

75/100A bit overcooked - sometimes, all you need is simplicity.Continue on AniListMusic anime with girl bands or groups being the focus have never been more prominent in the anime sphere, with recent hits like Bocchi the Rock, and old hits like K-On. In this season alone, we saw the revitalization of another old music hit in Sound! Euphonium Season 3, and new kids on the block in Girls Band Cry, and Jellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night. There’s so much that writers can do with this type of show, from stories of inspiration, stories of young people trying to find their passion, or in other cases, more comedy-oriented shows that serve to brighten up one’s day. In the end, the formula remains similar, to showcase the growth of the characters and their differing personalties, through their involvement in a music group.

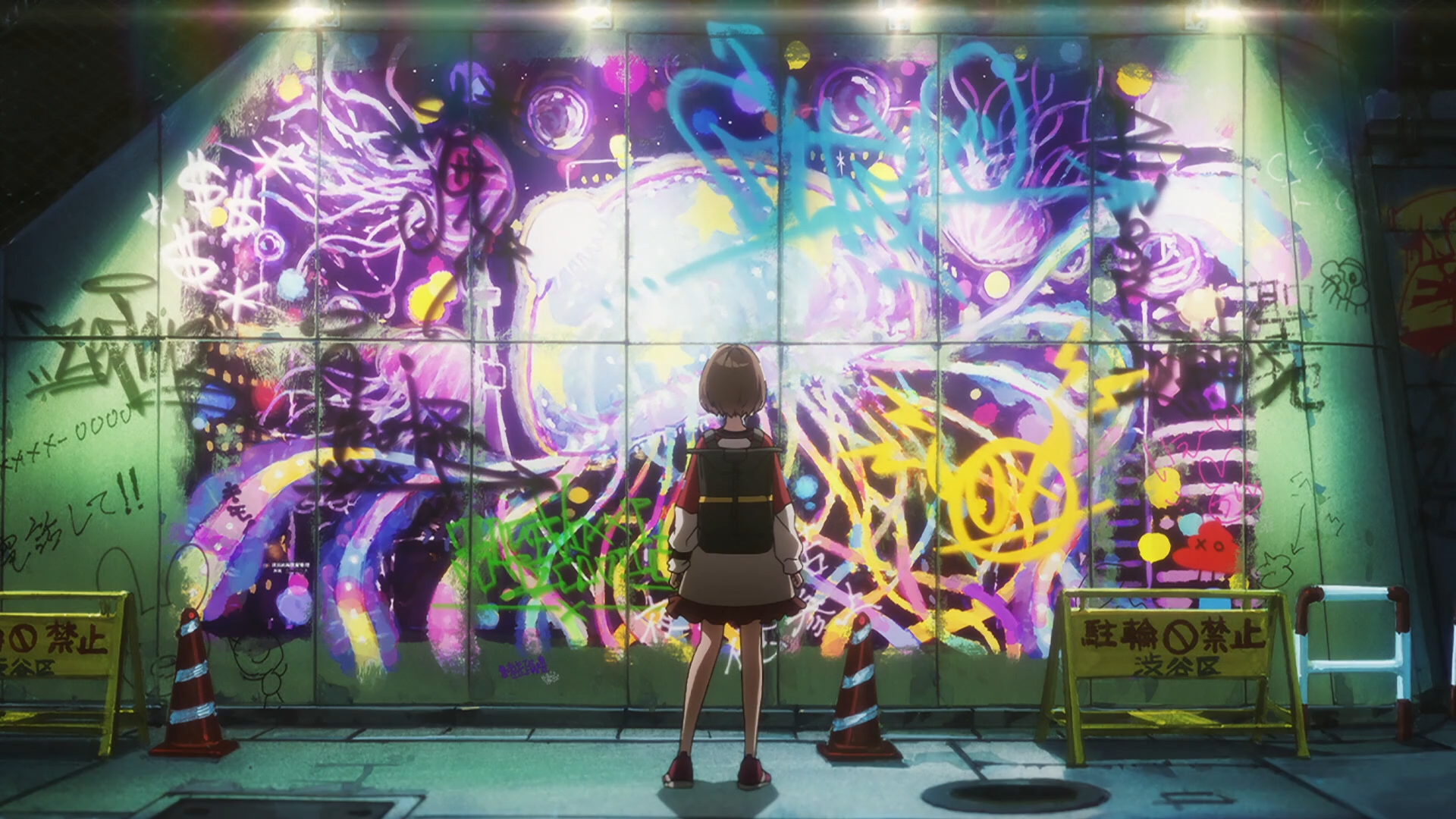

(Although formulaic, this genre and formula of girl bands is a canvas filled with so much possibility, just like Mahiru’s mural, which was pure imagination splattered on such a blank canvas, which is also what media creation is all about.) Jellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night is a bit of an odd case to me, because while it has its share of light-hearted moments, and the comedy is snappy and quite honestly, amazing at times, it also goes down the slippery slope of leaning into heavy melodrama. With the limited runtime that this had, with just twelve episodes, it was a bit of a questionable decision to me. In the first number of episodes, it was all about how people motivate each other, rather it was through art, music, or any other expressive outlet, and it was indeed very interesting. As the characters got introduced, they were characterized through various backstories that showed how tough their pasts were, or how they got to know other characters in the show. I’m not always a big fan of that story structure, as while it might provide great emotional highs, I’d much rather see the characters get characterized with how they act in the present, which this show does eventually do as well.

I call this an odd case, because each individual bit of character drama was honestly handled quite well, with very realistic and relatable struggles, for example, wanting to enjoy and behave in a way that people think is “childish”, or having one’s path to stardom broken because of a response to injustice. It led to some brilliant character chemistry between the members of JELEE for sure, but I also don’t think the drama contributed to the big picture of the story well enough, and also got in the way of what I expected the show to be more like, which was seeing the creative process of JELEE’s music.

To do all this in twelve episodes is no easy feat, and I just do not think there was enough time here to flesh everything out. The messages were really good, the pieces were there, but with twelve episodes, it was virtually impossible to fit in the progression of JELEE and the character drama, leading to various aspects feeling contrived and rushed, lacking the organic growth that we could have seen if this series had more of a runtime. JELEE gains a following in almost no time at all due to a timeskip, Mahiru’s art is suddenly highly respected from being mocked just a few episodes prior. Suddenly, a performance at a venue happens with not much build up. A career is put to a halt because of one single internet warrior. The antagonistic character suddenly goes along with what the protagonist proposes. You get my drift. Could this all have been fit into twelve episodes if the script was just a bit tighter? It’s hard to say how this anime should have went, because on the one hand, if you don’t have the comedy and light-hearted moments, the audience would not have as much of an attachment to the characters and their respective personalities, though on the other hand, if you don’t have the drama, the plot does not move forward. The best anime series are able to balance both the aspects of character building and pacing effectively. I do believe that the script could have been a bit tighter with the removal of a few characters, such as Baba and Koharu, so that the eventual drama could be less contrived. Again, I want to emphasize that the individual stories were good, but they just did not mesh well enough with each other. Some emphasis of side characters took away from Kano and Mahiru’s issues, and led to the overall storyline being resolved rather haphazardly.

Visually, this anime is stunning. Props to Ryouhei Takeshita for directing this as well as he did. It had a very snappy feeling in the editing made it a great vessel for comedic timing, which I still believe is the strongest part about this anime. I might not have agreed with some of the drama, but the way some of the dramatic scenes were directed was superb, along with the sound direction, to illicit as much emotion as they could out of the viewers. Furthermore, the voice acting performances here were excellent. Shout out to Rie Takahashi, Miyu Tomita, Miku Itou, and Miyuri Shimabukuro for their incredible work as Kano, Kiui, Mahiru, and Mei, respectively. There were also several music videos from JELEE that served as special ending themes, and you could see the improvement in the visuals with each passing music video. That type of subtle growth was what I wanted this anime to be like, but obviously, it went in a different direction.

(Credit to Asuka Suzuki, Takahashi Mizuki, Saurabh Singh, Shinnosuke Ota, Shuu Sugita, Anzu Yasue, Ayano Satou, and Kazuma Nakao for a great showcase of colours, camera angles, and vibrance for an excellent Shibuya-esque aesthetic. I would have wanted to see more opportunities for this to shine through.) With how solid the first few episodes were, I think it really showed that sometimes, things do not need to be deep and hugely thought-provoking to be good. The message was there, the characters were perfectly fine, the growth was JELEE was being seen, the comedy was snappy and funny, but the decision to go into heavy melodrama was one step I feel this anime did not need to take. The sheer energy of the show, the vibrance of the characters, all of that was sucked out with the melodrama, because even though the comedy still remained throughout, there was always that bit of drama that loomed large over it all, leaving it less fun than it could have been. It lacked a proper identity, and tried to do too much in a short amount of runtime.

In the end, it was like a slightly overcooked steak. It tastes good, but it is chewy, and leaves you slightly underwhelmed. Occasionally, some anime just have that sort of a fate. Oh, what this could have been…

planetJane

67/100Stylish, expressive, and deeply frustrating, the girls-do-music original escapes a simple, straightforward summation.Continue on AniList

All of my reviews contain __spoilers __for the reviewed material. This is your only warning.

We aren’t there yet, so it’s an educated guess at most, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the Spring 2024 season is remembered in hindsight as that of the yuri-inflected girl band series. You had the return of _Hibike Euphonium_, you had _Girls Band Cry_, you had _Whisper Me A Love Song_, for what little it contributed, but _Jellyfish Can’t Swim in The Night_ was, we’ll remember, there as well. For its first half dozen or so episodes, you could easily have argued that it was in fact the most beloved of all of the new entries here, as _Girls Band Cry_‘s anglosphere cult following had not yet reached fever pitch. In an even broader view, I wouldn’t be surprised if the long view of history lumps Jellyfish together with an even wider circle of anime; _Bocchi the Rock!_, _It’s MyGO_, whatever becomes of the Ave Mujica anime slated for next year, etc. Grouping all of these anime together is, of course, ultimately reductive, but something I’ve learned over the several years that I’ve been writing about anime is this; nothing escapes the context in which it is created. This is particularly unfair to _Jellyfish_ for a number of reasons, but one of them is that on a basic premise level, Jellyfish differs a bit from its contemporaries. JELEE, the “band” in _Jellyfish_, is really more of an arts collective centered around a pseudonymous vocalist. My immediate point of comparison was ZUTOMAYO, but really, any of the night scene bands that followed in their wake are a decent point of reference. Like some of those (but unlike ZTMY itself), JELEE’s membership is fairly small, consisting of vocalist Yamanouchi Kano [__Takahashi Rie__], composer and keyboardist Takanashi Kim Anouk Mei [__Shimabukuro Miyuri__], visual artist Kouzuki Mahiru, who also goes by Yoru [__Itou Miku__], and social media wizard Watase Kiui, who is also a VTuber under the name Nox Ryugasaki [__Tomita Miyu__]. The show is divided roughly into two parts, with the former half focused on JELEE coming together and then attempting to make a name for themselves, and the latter with the emotional fallout of Kano’s former career as an idol under the emotionally abusive management of her mother. Bluntly, the former works a lot better, and while there are a number of threads and subplots here, the ones that are successful share a certain verisimilitude. They focus more on things that seem like actual issues a contemporary pop group would encounter while trying to find a foothold in the uncaring ocean of the modern internet. These are generally simple. Some are pragmatic questions of how to get your music out there, others are more abstract and deal with things like finding artistic drive within yourself, being unashamed to express yourself for who you truly are, etc. The common element is pursuing your passions in a world that may be apathetic or even actively hostile to your doing so.

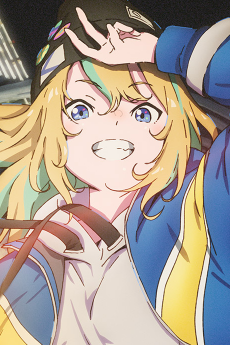

This takes different forms depending on the character. For Mahiru, who is perhaps the show’s “main protagonist” in as much as it really has one, it’s as simple as a lack of self-esteem and a tall order of impostor syndrome. For Kano, it’s significantly more complicated; she struggles to be noticed as an *utaite*, making cover songs in the aftermath of her failed idol career, there with a group called the Sunflower Dolls that she left under decidedly acrimonious terms after slugging one of the other members in the face. Mei and Kiui2 have it hard, too. We meet the former after years of burying herself in fandom for “Nonoka,” Kano’s old idol persona, as a coping method for dealing with the bullying she endured in school for being “weird” (read: neurodivergent) and for being biracial. We meet the latter, Mahiru’s childhood friend, constantly lying their ass off through the other side of a computer screen. Kiui spends most of the early show immersed in their VTuber persona and telling tall tales about how popular they are at school and such. (They aren’t.)

_Jellyfish_ splits its time unevenly between these characters—not inherently an issue—with most of the early show focusing on Mahiru and most of the latter half of the series focusing on Kano. It’s not a clean split, as episodes primarily about Kiui are sprinkled throughout. Mei gets the short end of the stick, with only her introductory episode and a handful of stray scenes later on really focusing on her as a person.

For the first part of the show, the main thrust of the plot is the formation of JELEE itself, the arts collective that the girls create as a vehicle for Kano’s singing, Mei’s composition, and Mahiru’s visual art. JELEE finds a fair amount of early success, and this early phase of the show hits its peak during one of Mahiru’s bouts of self-doubt. Admitting that she resents that other artists can draw JELEE-chan—the jellyfish-themed mascot she created for the group—better than she can, she and Kano have a heart to heart in the snow, and Kano kisses Mahiru on the cheek. (Followups to that particular development are indirect, manifesting in such forms as Mahiru gently teasing her about it an episode or two later.)

Throughout all of this, the traumatic fallout from Kano’s previous career as an idol remains a lurking background element, but it’s only when her mother, Yukine [Kaida Yuuko], is properly introduced as a character, a fair ways into the anime, that it really becomes a central focus, and the anime shifts gears to reorient around this. It’s hard to call this change in direction a mistake, exactly, since it leads to some of the anime’s best scenes, and probably its overall best episode in its ninth, but it’s definitely a stark change, and the show handles it unevenly.

Throughout the ninth episode, we get flashbacks of how Kano came to be the original center for the Sunflower Dolls and how she was eventually kicked out of the group. Here, Kano becomes “Nonoka.” Her mother controls her style and manipulates her talents for her own ends in a plainly vile way that paints a very clear picture of her as an old-school slimeball record exec. Really, the moment that seals the deal in hindsight is when she lays out her goals to Kano. *“I want to one day nurture an artist who sings to 50,000 people.”* (*Jellyfish* floats a lot of numbers around over the course of its runtime, but that one, the 50,000 associated with the maximum seating capacity of the Tokyo Dome, is the one it runs back most frequently.) Unfortunately, Kano’s time with the Sunflower Dolls comes to an unceremonious end when she discovers that Mero, one of the other girls in the group, has been running a Youtube page that spreads gossip and inflames scandals about rival acts. Enraged, Kano punches her—the incident we’ve known about for the whole show, but only then get the full context for—and her career in the traditional idol industry ends in an instant. She’s so overcome with shame and emotion that the show actually switches art styles. In a compelling, lightly experimental touch, the visuals seem to turn into something like a burning oil painting, as though Kano is physically igniting under the harsh, dispassionate glare of her mother.

This takes different forms depending on the character. For Mahiru, who is perhaps the show’s “main protagonist” in as much as it really has one, it’s as simple as a lack of self-esteem and a tall order of impostor syndrome. For Kano, it’s significantly more complicated; she struggles to be noticed as an *utaite*, making cover songs in the aftermath of her failed idol career, there with a group called the Sunflower Dolls that she left under decidedly acrimonious terms after slugging one of the other members in the face. Mei and Kiui2 have it hard, too. We meet the former after years of burying herself in fandom for “Nonoka,” Kano’s old idol persona, as a coping method for dealing with the bullying she endured in school for being “weird” (read: neurodivergent) and for being biracial. We meet the latter, Mahiru’s childhood friend, constantly lying their ass off through the other side of a computer screen. Kiui spends most of the early show immersed in their VTuber persona and telling tall tales about how popular they are at school and such. (They aren’t.)

_Jellyfish_ splits its time unevenly between these characters—not inherently an issue—with most of the early show focusing on Mahiru and most of the latter half of the series focusing on Kano. It’s not a clean split, as episodes primarily about Kiui are sprinkled throughout. Mei gets the short end of the stick, with only her introductory episode and a handful of stray scenes later on really focusing on her as a person.

For the first part of the show, the main thrust of the plot is the formation of JELEE itself, the arts collective that the girls create as a vehicle for Kano’s singing, Mei’s composition, and Mahiru’s visual art. JELEE finds a fair amount of early success, and this early phase of the show hits its peak during one of Mahiru’s bouts of self-doubt. Admitting that she resents that other artists can draw JELEE-chan—the jellyfish-themed mascot she created for the group—better than she can, she and Kano have a heart to heart in the snow, and Kano kisses Mahiru on the cheek. (Followups to that particular development are indirect, manifesting in such forms as Mahiru gently teasing her about it an episode or two later.)

Throughout all of this, the traumatic fallout from Kano’s previous career as an idol remains a lurking background element, but it’s only when her mother, Yukine [Kaida Yuuko], is properly introduced as a character, a fair ways into the anime, that it really becomes a central focus, and the anime shifts gears to reorient around this. It’s hard to call this change in direction a mistake, exactly, since it leads to some of the anime’s best scenes, and probably its overall best episode in its ninth, but it’s definitely a stark change, and the show handles it unevenly.

Throughout the ninth episode, we get flashbacks of how Kano came to be the original center for the Sunflower Dolls and how she was eventually kicked out of the group. Here, Kano becomes “Nonoka.” Her mother controls her style and manipulates her talents for her own ends in a plainly vile way that paints a very clear picture of her as an old-school slimeball record exec. Really, the moment that seals the deal in hindsight is when she lays out her goals to Kano. *“I want to one day nurture an artist who sings to 50,000 people.”* (*Jellyfish* floats a lot of numbers around over the course of its runtime, but that one, the 50,000 associated with the maximum seating capacity of the Tokyo Dome, is the one it runs back most frequently.) Unfortunately, Kano’s time with the Sunflower Dolls comes to an unceremonious end when she discovers that Mero, one of the other girls in the group, has been running a Youtube page that spreads gossip and inflames scandals about rival acts. Enraged, Kano punches her—the incident we’ve known about for the whole show, but only then get the full context for—and her career in the traditional idol industry ends in an instant. She’s so overcome with shame and emotion that the show actually switches art styles. In a compelling, lightly experimental touch, the visuals seem to turn into something like a burning oil painting, as though Kano is physically igniting under the harsh, dispassionate glare of her mother.

All of this portrays Kano as a victim in an industry that is certainly no stranger to victimizing even its youngest performers, and paints Yukine as, at best, deeply callous about her daughter’s suffering, and at worst, an outright abusive figure, a gender-flipped version of the archetypal sinister record executive-patriarch. It’ll make you want to scream “leave Kano alone!” at your TV, if you’re anything like me.

It’s worth noting that all of these flashbacks are broadly from Kano’s own point of view, but there’s relatively little evidence of some kind of unreliable narrator thing going on, and the trauma Kano endures from all of these events is obviously very real. This is unfortunate in its own way, because it feeling so raw and so emotionally resonant means that when the show tries to tie Kano and Yukine’s relationship up with minimal fuss in the last episode it really doesn’t work, as we’ll come back to. And as a further side note; we have no reason to directly suspect that Yukine was encouraging Mero’s little side activity in running the Youtube channel, but it so clearly seems like the kind of thing she’d do, given what little we have to go on, that I have a hard time imagining at least some of the story here isn’t trying to imply that.

Back in the show’s present, Yukine approaches Mahiru with an offer to do some visual work for the current incarnation of the Sunflower Dolls. (One with Mero as the center, mind you.) Yukine certainly seems to have ulterior motives for doing this, and when Mahiru tells Kano about her plans to take the job offer—pushing back a release of one of JELEE’s own songs in the process—Kano absolutely blows up at her, calling Mahiru a liar and ranting about how she’s the only reason anyone knows Mahiru’s art in the first place. It is legitimately hard to watch, and in the moment, it made quite the strong impression on me. (Especially when coupled with the absolutely diabolical editing decision to have that episode’s outro mostly be a montage of the two calling each other’s names.) With hindsight though, I actually think this is where *Jellyfish* starts to fall apart. Kano and Mahiru don’t really get many scenes together in the episodes after this, and those that do are brief and feel unsatisfying. Is that realistic? Sure, maybe, and if the series wanted to lean in to the emotional hurt there, and make it seem like these two would never be close again, that would also be a valid artistic decision. The problem is that it doesn’t really do either of these things, as we’ll circle back to.

Not every plot the show tries is derailed in this manner, of course. Kiui gets a great arc wherein they manage to overcome some of their severe social anxiety. The work with JELEE brings them out of their shell somewhat, but they really begin to undergo some proper character development during a small arc where they’re attempting to get a motorcycle license, staying at a driving school for a time, with Kano, in pursuit of that goal. There, they meet an older woman named Koharu [Seto Asami]. Koharu is an interesting, if minor figure in *Jellyfish*, an all-but-outright-stated-to-be-trans woman who’s an implied former yakuza and who hits on Kiui basically as soon as they show up. The two hit it off, and their budding romance is a very small but legitimately sweet part of the show, and the few conversations they have over the course of the series feel very lived-in, especially when they get into nerdy areas of discussion like denpa visual novels and the like. (Even this isn’t perfect and I might rewrite some of Koharu’s dialogue, to put it mildly, but you take what you can get with these things.)

Kiui even gets what is probably the last great moment in the series. In episode 11, they and Mahiru are at an arcade and run into some former classmates of theirs. *Jellyfish* takes a moment to get extremely real here, as the kids hate Kiui not just for how they’re generally “weird” but also for their apparent lack of conforming to the gender binary.

All of this portrays Kano as a victim in an industry that is certainly no stranger to victimizing even its youngest performers, and paints Yukine as, at best, deeply callous about her daughter’s suffering, and at worst, an outright abusive figure, a gender-flipped version of the archetypal sinister record executive-patriarch. It’ll make you want to scream “leave Kano alone!” at your TV, if you’re anything like me.

It’s worth noting that all of these flashbacks are broadly from Kano’s own point of view, but there’s relatively little evidence of some kind of unreliable narrator thing going on, and the trauma Kano endures from all of these events is obviously very real. This is unfortunate in its own way, because it feeling so raw and so emotionally resonant means that when the show tries to tie Kano and Yukine’s relationship up with minimal fuss in the last episode it really doesn’t work, as we’ll come back to. And as a further side note; we have no reason to directly suspect that Yukine was encouraging Mero’s little side activity in running the Youtube channel, but it so clearly seems like the kind of thing she’d do, given what little we have to go on, that I have a hard time imagining at least some of the story here isn’t trying to imply that.

Back in the show’s present, Yukine approaches Mahiru with an offer to do some visual work for the current incarnation of the Sunflower Dolls. (One with Mero as the center, mind you.) Yukine certainly seems to have ulterior motives for doing this, and when Mahiru tells Kano about her plans to take the job offer—pushing back a release of one of JELEE’s own songs in the process—Kano absolutely blows up at her, calling Mahiru a liar and ranting about how she’s the only reason anyone knows Mahiru’s art in the first place. It is legitimately hard to watch, and in the moment, it made quite the strong impression on me. (Especially when coupled with the absolutely diabolical editing decision to have that episode’s outro mostly be a montage of the two calling each other’s names.) With hindsight though, I actually think this is where *Jellyfish* starts to fall apart. Kano and Mahiru don’t really get many scenes together in the episodes after this, and those that do are brief and feel unsatisfying. Is that realistic? Sure, maybe, and if the series wanted to lean in to the emotional hurt there, and make it seem like these two would never be close again, that would also be a valid artistic decision. The problem is that it doesn’t really do either of these things, as we’ll circle back to.

Not every plot the show tries is derailed in this manner, of course. Kiui gets a great arc wherein they manage to overcome some of their severe social anxiety. The work with JELEE brings them out of their shell somewhat, but they really begin to undergo some proper character development during a small arc where they’re attempting to get a motorcycle license, staying at a driving school for a time, with Kano, in pursuit of that goal. There, they meet an older woman named Koharu [Seto Asami]. Koharu is an interesting, if minor figure in *Jellyfish*, an all-but-outright-stated-to-be-trans woman who’s an implied former yakuza and who hits on Kiui basically as soon as they show up. The two hit it off, and their budding romance is a very small but legitimately sweet part of the show, and the few conversations they have over the course of the series feel very lived-in, especially when they get into nerdy areas of discussion like denpa visual novels and the like. (Even this isn’t perfect and I might rewrite some of Koharu’s dialogue, to put it mildly, but you take what you can get with these things.)

Kiui even gets what is probably the last great moment in the series. In episode 11, they and Mahiru are at an arcade and run into some former classmates of theirs. *Jellyfish* takes a moment to get extremely real here, as the kids hate Kiui not just for how they’re generally “weird” but also for their apparent lack of conforming to the gender binary.

Kiui, in a minor moment of triumph, gathers the inner conviction to tell them off by tapping into her own VTuber persona, which, they seem to realize in doing so, is in some ways more “real” than their outward physical self. That kind of thing, with a constructed persona that feels more in tune with “who you really are” than your actual body does, is extremely common among a certain kind of internet-native queer person. I’m speaking from experience here, and I think this plot is probably the best single thing that *Jellyfish* pulls off. Making people feel seen is valuable.

Kiui, in a minor moment of triumph, gathers the inner conviction to tell them off by tapping into her own VTuber persona, which, they seem to realize in doing so, is in some ways more “real” than their outward physical self. That kind of thing, with a constructed persona that feels more in tune with “who you really are” than your actual body does, is extremely common among a certain kind of internet-native queer person. I’m speaking from experience here, and I think this plot is probably the best single thing that *Jellyfish* pulls off. Making people feel seen is valuable.

Mahiru and Kano’s ongoing tension, meanwhile, goes largely unaddressed during all of this, and they appear to forgive each other in the final episode—after the big, emotional finale, which, with a few days of hindsight behind me, feels quite flat—based on….vibes, I suppose? They don’t really talk anything out! And I’m not the sort of person to demand lengthy on-screen Healthy Emotional Communication, but something a bit more substantial than the little we get here would be nice, and that really is my central problem with *Jellyfish*. It has all of these moments that are good to great, but they don’t cohere, because the show either can’t make them fit together in a way that feels holistic or it simply drops them entirely.

Mahiru and Kano’s ongoing tension, meanwhile, goes largely unaddressed during all of this, and they appear to forgive each other in the final episode—after the big, emotional finale, which, with a few days of hindsight behind me, feels quite flat—based on….vibes, I suppose? They don’t really talk anything out! And I’m not the sort of person to demand lengthy on-screen Healthy Emotional Communication, but something a bit more substantial than the little we get here would be nice, and that really is my central problem with *Jellyfish*. It has all of these moments that are good to great, but they don’t cohere, because the show either can’t make them fit together in a way that feels holistic or it simply drops them entirely.

If I had to guess, what *Jellyfish* wants to do is use this act of simply stopping at a certain point as a statement unto itself. In the last moments of the show there are clearly still some unaddressed problems. Kano, for instance, obsesses over her performance in the finale being seen by over 50,000 people—that magic number her mom planted in her head as a kid—and the rest of JELEE are rightly weirded out by the whole thing. But we’re clearly also supposed to feel that this is essentially a happy ending for them, as the show’s last real scene is JELEE banding together to paint over the jellyfish mural—an old piece of Mahiru’s art—that inspired their endeavor to begin with. It’s beautifully drawn and composed, and it tries so hard to sell these big emotions, but it feels almost perfunctory, regardless. As though *Jellyfish* is doing this because it can’t stomach showing us an actual unhappy ending, or because it thinks we’d be angry if it did so.

Whether one wants to see *Jellyfish* as an anime that is sabotaged by this flaw or one that manages to work in spite of it is largely a matter of perspective. Can you ignore Yukine’s abuse going unaddressed? Can you ignore that the show never circles back around to Mero torpedo’ing the careers of the Rainbow Girls? Can you ignore the unshakeable feeling that this whole thing really needed another six episodes or so to really breathe? That it really clearly does not have the space to do everything it wants to do? All of that is going to depend on the person. For some, this is going to come off as extreme nitpicking and I will seem very shrill. I must again stress however that I’m fine with these things not being solved on-screen, I just want the show to follow up on them, any of them, in some form.

For me, the clearly stitched-together nature of the writing in the show’s latter half kills much of the emotional resonance I felt in its best moments. Some anime are camp enough, strange enough, or challenging enough to get away with ending on what’s essentially a shrug. If it clicked enough with you, you can say “well, the show is messy” and declare its flaws ignorable. Unfortunately, the emotional math involved here just doesn’t work for me. The fact that the Rainbow Girls are not characters in this narrative because we’re just supposed to write them off after their single appearance does not work for me. The fact that Kano and Mero never even really directly talk, but that we’re clearly supposed to assume they’ve somehow reconciled does not work for me. The fact that Kano and Mahiru are, in fact, entirely kept apart for most of the show’s final third does not work for me. The fact that Kano’s lack of forgiveness to her mother is signified by nothing more than playfully brushing her off in the show’s closing minutes after she sends a goddamn limo to Kano’s school does not work for me. None of this works for me! That’s really frustrating!

If I had to guess, what *Jellyfish* wants to do is use this act of simply stopping at a certain point as a statement unto itself. In the last moments of the show there are clearly still some unaddressed problems. Kano, for instance, obsesses over her performance in the finale being seen by over 50,000 people—that magic number her mom planted in her head as a kid—and the rest of JELEE are rightly weirded out by the whole thing. But we’re clearly also supposed to feel that this is essentially a happy ending for them, as the show’s last real scene is JELEE banding together to paint over the jellyfish mural—an old piece of Mahiru’s art—that inspired their endeavor to begin with. It’s beautifully drawn and composed, and it tries so hard to sell these big emotions, but it feels almost perfunctory, regardless. As though *Jellyfish* is doing this because it can’t stomach showing us an actual unhappy ending, or because it thinks we’d be angry if it did so.

Whether one wants to see *Jellyfish* as an anime that is sabotaged by this flaw or one that manages to work in spite of it is largely a matter of perspective. Can you ignore Yukine’s abuse going unaddressed? Can you ignore that the show never circles back around to Mero torpedo’ing the careers of the Rainbow Girls? Can you ignore the unshakeable feeling that this whole thing really needed another six episodes or so to really breathe? That it really clearly does not have the space to do everything it wants to do? All of that is going to depend on the person. For some, this is going to come off as extreme nitpicking and I will seem very shrill. I must again stress however that I’m fine with these things not being solved on-screen, I just want the show to follow up on them, any of them, in some form.

For me, the clearly stitched-together nature of the writing in the show’s latter half kills much of the emotional resonance I felt in its best moments. Some anime are camp enough, strange enough, or challenging enough to get away with ending on what’s essentially a shrug. If it clicked enough with you, you can say “well, the show is messy” and declare its flaws ignorable. Unfortunately, the emotional math involved here just doesn’t work for me. The fact that the Rainbow Girls are not characters in this narrative because we’re just supposed to write them off after their single appearance does not work for me. The fact that Kano and Mero never even really directly talk, but that we’re clearly supposed to assume they’ve somehow reconciled does not work for me. The fact that Kano and Mahiru are, in fact, entirely kept apart for most of the show’s final third does not work for me. The fact that Kano’s lack of forgiveness to her mother is signified by nothing more than playfully brushing her off in the show’s closing minutes after she sends a goddamn limo to Kano’s school does not work for me. None of this works for me! That’s really frustrating!

Let’s circle back to the term *“messy”*, in fact. “Messy” is often used, as a descriptor, to smooth over the rough edges of art we love. A way to excuse conflict and problematica because the art resonates hard enough with us that we have cause to explain its uncomfortable aspects away. You could call *Jellyfish* “messy,” for certain, and there are parts of it I’d apply that label to (Koharu and Kiui’s relationship, perhaps), but for the most part there’s not a lot of what I’d call messiness in *Jellyfish*. All of these aspects that don’t work are not messy, they’re just some shit that happens that the show gets in over its head in trying to address. This is why it feels unsatisfying on the whole despite a number of strong moments. The actual tone the show is going for gets lost somewhere in the shuffle.

Let’s circle back to the term *“messy”*, in fact. “Messy” is often used, as a descriptor, to smooth over the rough edges of art we love. A way to excuse conflict and problematica because the art resonates hard enough with us that we have cause to explain its uncomfortable aspects away. You could call *Jellyfish* “messy,” for certain, and there are parts of it I’d apply that label to (Koharu and Kiui’s relationship, perhaps), but for the most part there’s not a lot of what I’d call messiness in *Jellyfish*. All of these aspects that don’t work are not messy, they’re just some shit that happens that the show gets in over its head in trying to address. This is why it feels unsatisfying on the whole despite a number of strong moments. The actual tone the show is going for gets lost somewhere in the shuffle.

The show attempts to do right by its queer audience in spite of all this; mostly in terms of Kiui’s subplot, but I think people have been a little unfair in labeling the show ‘queerbaity’ in the fairly subtle way it handles Mahiru and Kano’s relationship, as well. This, and the other more general ways the series fails to come together, creates a situation that practically begs for baseless, conspiratorial thinking. Did some suit decide the show was Too Gay, prompting a last-minute rewrite? Was there some kind of cut in episode number that impacted the narrative? Did network censors object? There’s no actual reason to believe these things, but they are the sort of theorizing that tends to pop up in the wake of an anime ending like this, because it’s an explanation. An explanation, no matter how convoluted, seems to make more sense than what appears to be the actual case; the show just faceplanted in its final stretch without a single specific cause. It happens. My personal theory is that primary scriptwriter __Yaku Yuki__, best known as the novelist behind *Bottom-tier Character Tomozaki*, had trouble adapting to the switch in format. There’s not really any more evidence for this than any of these other theories, but it would make sense, and would account for the show’s sometimes cramped and overstuffed writing. (In fact, I have somehow gone this entire review without mentioning the weird little side plot of Miiko [Uesaka Sumire], the 30-something idol that JELEE butt heads with a few times and eventually become friends with. The whole plot is actually pretty much fine, if not necessarily a highlight of the show. But a longer anime could have things like that without it feeling so incongruous with the rest of the series.)

I’ve spent a lot of time wracking my brain about what exactly my takeaway from *Jellyfish* has been without simply turning in basic qualitative assessments. It’s true that it’s probably always going to be considered in the broader “girl band anime” context, and that it isn’t the best series in that subgenre by any means. (I will also quickly make the point that, on the other hand, this is not a *Metallic Rouge* situation where hindsight makes it clear that the show never had any idea of what it was doing.) But putting it in those terms feels incredibly reductive! I’ve said a lot that’s negative about the show, but there is a lot to like as well! Visually, it’s pretty damn incredible! I’ve already mentioned its shift into a moving oil painting during one of Kano’s flashbacks, but it uses quite a few interesting tricks throughout, from video effects like a simulated VHS tape in the first episode, being drawn as though shot on a smartphone in the last, to rapid animation cuts to signify time passing quickly (often because Mei is enthusing over something), there’s a good amount to enjoy here in the visual dimension. The soundtrack is great, too! While I wasn’t enthused about JELEE’s music for the most part, the actual BGM is a weird, synth-heavy, analog-sounding thing that burbles and strains and hums expressively throughout essentially the whole show.

The show attempts to do right by its queer audience in spite of all this; mostly in terms of Kiui’s subplot, but I think people have been a little unfair in labeling the show ‘queerbaity’ in the fairly subtle way it handles Mahiru and Kano’s relationship, as well. This, and the other more general ways the series fails to come together, creates a situation that practically begs for baseless, conspiratorial thinking. Did some suit decide the show was Too Gay, prompting a last-minute rewrite? Was there some kind of cut in episode number that impacted the narrative? Did network censors object? There’s no actual reason to believe these things, but they are the sort of theorizing that tends to pop up in the wake of an anime ending like this, because it’s an explanation. An explanation, no matter how convoluted, seems to make more sense than what appears to be the actual case; the show just faceplanted in its final stretch without a single specific cause. It happens. My personal theory is that primary scriptwriter __Yaku Yuki__, best known as the novelist behind *Bottom-tier Character Tomozaki*, had trouble adapting to the switch in format. There’s not really any more evidence for this than any of these other theories, but it would make sense, and would account for the show’s sometimes cramped and overstuffed writing. (In fact, I have somehow gone this entire review without mentioning the weird little side plot of Miiko [Uesaka Sumire], the 30-something idol that JELEE butt heads with a few times and eventually become friends with. The whole plot is actually pretty much fine, if not necessarily a highlight of the show. But a longer anime could have things like that without it feeling so incongruous with the rest of the series.)

I’ve spent a lot of time wracking my brain about what exactly my takeaway from *Jellyfish* has been without simply turning in basic qualitative assessments. It’s true that it’s probably always going to be considered in the broader “girl band anime” context, and that it isn’t the best series in that subgenre by any means. (I will also quickly make the point that, on the other hand, this is not a *Metallic Rouge* situation where hindsight makes it clear that the show never had any idea of what it was doing.) But putting it in those terms feels incredibly reductive! I’ve said a lot that’s negative about the show, but there is a lot to like as well! Visually, it’s pretty damn incredible! I’ve already mentioned its shift into a moving oil painting during one of Kano’s flashbacks, but it uses quite a few interesting tricks throughout, from video effects like a simulated VHS tape in the first episode, being drawn as though shot on a smartphone in the last, to rapid animation cuts to signify time passing quickly (often because Mei is enthusing over something), there’s a good amount to enjoy here in the visual dimension. The soundtrack is great, too! While I wasn’t enthused about JELEE’s music for the most part, the actual BGM is a weird, synth-heavy, analog-sounding thing that burbles and strains and hums expressively throughout essentially the whole show.

Generally speaking, the show is very stylish! The first episode in particular is a masterclass in visual storytelling! And even back on the writing end, the series’ portrayal of the suffocating smoke of having a controlling parent be absolutely furious with you is spot on! Kano pecking Mahiru on the cheek seriously does matter even if the followup isn’t as strong as we may have wanted it to be! Kiui’s complex gender identity is some of the best representation of its type I’ve ever seen in an anime! All of this is just as true as the show’s more frustrating aspects, and I think if the series develops a cult following in the years to come (and I would be unsurprised to see that happen) it will be off of these strengths. Those people will watch *Jellyfish* in a different way than I did. It’s true that nothing really escapes the context it’s created in, but we often only have a clear picture of that context in hindsight. Maybe, somewhere between all the aspects that frustrated me so much, is a better show that is only visible with some remove.

So that’s where we’re at. I wanted to like *Jellyfish* more than I did, and that’s admittedly an annoying position to be in. Because I simultaneously feel like I’m giving the show more of a pass than I should be and also being way too hard on it. But that’s the way things go sometimes! If any part of *Jellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night* is truly encapsulated by the term ‘messy,’ it might be that very relationship that I, and many other viewers, have to the series in of itself. It’s obvious, but, sometimes art is not strictly good or bad! Sometimes it gets in your head in a way that causes you to spout a gushing torrent of thoughts that only barely cohere and sometimes outright contradict each other. I have said things of this nature many times on this blog, and I’ll probably say them many times more. Maybe, if all *Jellyfish* wanted to do was leave an impression—to shine a little, to borrow Mahiru’s own words—then my big judgy opinion about whether it’s *peak or mid, man*, matters less than the fact that it made me think this much about it at all. Jellyfish can’t swim, night or day. But sometimes it’s nice to just drift in the currents of the ocean and let them take you where they will; you can’t complain too much about choppy waters.

Generally speaking, the show is very stylish! The first episode in particular is a masterclass in visual storytelling! And even back on the writing end, the series’ portrayal of the suffocating smoke of having a controlling parent be absolutely furious with you is spot on! Kano pecking Mahiru on the cheek seriously does matter even if the followup isn’t as strong as we may have wanted it to be! Kiui’s complex gender identity is some of the best representation of its type I’ve ever seen in an anime! All of this is just as true as the show’s more frustrating aspects, and I think if the series develops a cult following in the years to come (and I would be unsurprised to see that happen) it will be off of these strengths. Those people will watch *Jellyfish* in a different way than I did. It’s true that nothing really escapes the context it’s created in, but we often only have a clear picture of that context in hindsight. Maybe, somewhere between all the aspects that frustrated me so much, is a better show that is only visible with some remove.

So that’s where we’re at. I wanted to like *Jellyfish* more than I did, and that’s admittedly an annoying position to be in. Because I simultaneously feel like I’m giving the show more of a pass than I should be and also being way too hard on it. But that’s the way things go sometimes! If any part of *Jellyfish Can’t Swim in the Night* is truly encapsulated by the term ‘messy,’ it might be that very relationship that I, and many other viewers, have to the series in of itself. It’s obvious, but, sometimes art is not strictly good or bad! Sometimes it gets in your head in a way that causes you to spout a gushing torrent of thoughts that only barely cohere and sometimes outright contradict each other. I have said things of this nature many times on this blog, and I’ll probably say them many times more. Maybe, if all *Jellyfish* wanted to do was leave an impression—to shine a little, to borrow Mahiru’s own words—then my big judgy opinion about whether it’s *peak or mid, man*, matters less than the fact that it made me think this much about it at all. Jellyfish can’t swim, night or day. But sometimes it’s nice to just drift in the currents of the ocean and let them take you where they will; you can’t complain too much about choppy waters.

***Notes & Disclaimers*** *Usage of Anilist's review feature does not constitute endorsement for Anilist as a platform, the Anilist community or any individual member thereof, or any of Anilist's policies or rules.* *All views expressed are solely my own opinions and conclusions and should not be taken to reflect the opinions of any other persons, groups, or organizations. All text is owned by me. Do not duplicate without permission. All images are owned by their original copyright holders.* *This review has been reformatted and re-edited to comply with Anilist's site guidelines.*

SIMILAR ANIMES YOU MAY LIKE

ANIME AdventureSora yori mo Tooi Basho

ANIME AdventureSora yori mo Tooi Basho ANIME ComedyParipi Koumei

ANIME ComedyParipi Koumei ANIME ComedyYofukashi no Uta

ANIME ComedyYofukashi no Uta ANIME DramaGIRLS BAND CRY

ANIME DramaGIRLS BAND CRY![[Oshi no Ko] Cover Art for [Oshi no Ko]](https://s4.anilist.co/file/anilistcdn/media/anime/cover/medium/bx150672-jguvEfP0vGfW.png) ANIME Drama[Oshi no Ko]

ANIME Drama[Oshi no Ko] ANIME ComedyBocchi the Rock!

ANIME ComedyBocchi the Rock! ANIME ActionWonder Egg Priority

ANIME ActionWonder Egg Priority ANIME ActionFlip Flappers

ANIME ActionFlip Flappers ANIME DramaHibike! Euphonium

ANIME DramaHibike! Euphonium ANIME ComedyKuragehime

ANIME ComedyKuragehime ANIME DramaCarole & Tuesday

ANIME DramaCarole & Tuesday

SCORE

- (3.85/5)

TRAILER

MORE INFO

Ended inJune 23, 2024

Main Studio Doga Kobo

Trending Level 2

Favorited by 1,181 Users

Hashtag #ヨルクラ #YORUKURA_ANIME