GED SENKI

MOVIE

Dubbed

SOURCE

OTHER

RELEASE

July 29, 2006

LENGTH

115 min

DESCRIPTION

In the land of Earthsea, crops are dwindling, dragons have reappeared, and humanity is giving way to chaos. Journey with Lord Archmage Sparrowhawk, a master wizard, and Arren, a troubled young prince, on a tale of redemption and self-discovery as they search for the force behind the mysterious imbalance that threatens to destroy their world.

(Source: Disney)

CAST

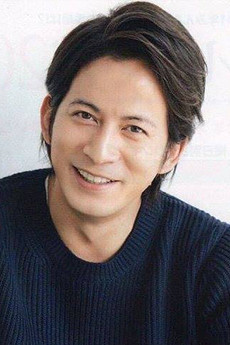

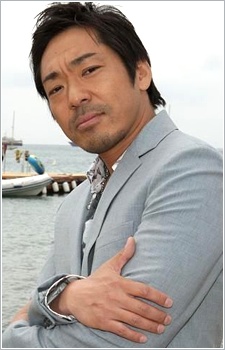

Arren

Junichi Okada

Therru

Aoi Teshima

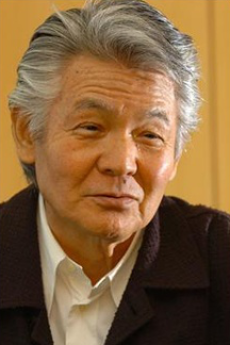

Ged

Bunta Sugawara

Tenar

Jun Fubuki

Kumo

Yuko Tanaka

Usagi

Teruyuki Kagawa

Kokuou

Kaoru Kobayashi

Ouhi

Yui Natsukawa

RELATED TO GED SENKI

MANGA ActionShuna no Tabi

MANGA ActionShuna no TabiREVIEWS

hoeberries

30/100Daddy Issues: A Freudian Autopsy of Goro MiyazakiContinue on AniListPatricide.

Yeah, I said it. Just keep that word in mind while I rattle off some backstory for this thing.

Tales From Earthsea (2006) is generally considered the worst Studio Ghibli movie, which I guess is no longer the case now that Earwig and the Witch (2020) exists. The biggest thing that these two movies have in common, apart from being disappointing, is that they are directed by Goro Miyazaki, son of Hayao Miyazaki, who really still has no business directing an animated feature.

But let’s backtrack. How did Goro end up in his first role? How did this movie come to be? Spoilers ahead for the inner workings of Goro's mind.

Hayao Miyazaki had been writing to Ursula K Le Guin for like thirty years, begging and pleading for the opportunity to adapt her series of Earthsea books to film. Because she thought Ghibli was the Japanese Disney, she always told him to leave her alone… until, like, twenty years later, when she watched My Neighbour Totoro (1988) and realised she had to get on that Miyazaki train. He was a legitimate auteur, and his style fit Earthsea to a tee! She contacted Ghibli and even sanctioned off this period in between the first and second Earthsea books, allowing them to basically do whatever they wanted. This was perfect for a director like Miyazaki, who prefers to do his own thing with source material rather than stick to a rigid adaptation.

Unfortunately, by this point Miyazaki was messing with Diana Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle (1986) (traitor!) and totally 100% trust-me-on-this-one retiring soon, so he wasn’t available. Toshio Suzuki, former president of Ghibli, decided it would be a fantastic idea to contact Miyazaki’s son and smooth-talk the kid into doing Earthsea instead, thereby turning one of the most beloved and respected children’s series into a long and ambitious film. You know, putting aside the fact that he’d never drawn a frame in his life and all.

Goro got done dirty. The fact that he ended up directing Tales From Earthsea is nothing less than an astonishing act of nepotism that was wholly undeserved and entirely irresponsible, but it wasn’t as if he demanded the job. He started as a mere consultant. Before that, he was off studying landscape design, convinced that he hated animation.

But really, he just hated his dad. You see, Hayao Miyazaki was always busy with his movies, so Goro didn’t have the best relationship with him growing up. It was only after he was roped into designing some part of the Ghibli museum that he realised he might actually have some latent love for the medium, stating in his blog that “I had discovered within myself a love of animation which, because of my relationship with my father, I had pretended for a long time not to notice, until now.” He also had a special affinity to the Earthsea series, having grown up with the books.

Alas, it was a rocky journey. Miyazaki senior was furious that someone with no directorial experience was occupying such an important role. He threw this big tantrum, planned an animator strike as an act of elaborate sabotage, and barely talked to his son during what had to be the most stressful period of the kid’s life. What a guy. Father of the century. Against insurmountable odds, Goro finished the movie on schedule.

It wasn’t exactly a roaring success. His father talked a bunch of shit, Ursula K Le Guin talked a bunch more shit, and fans were pretty underwhelmed. He even received the Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Movie, beating out Sinking of Japan (2006), which is literally an adaptation Japan Sinks (1973) without Masaaki Yuasa's artsy shit tricking you into thinking it's good.

You have to feel a bit sorry for Goro.

Anyway, I sit down to watch this movie, fully expecting it to suck (and, by all means, it kind of does). There are some random dragons flying around, this generic fantasy setting that doesn’t really capture the Earthsea magic… and then this kid just straight-up murders his father. That’s it. That’s the opener.

As the movie goes on, we learn his father was a “great man” who made the kid feel intensely inadequate; however, because the dad was the king of our generic fantasy country, we can assume he didn’t have all that much to do with his attention-craving son (until said son took a sword and ran it through his stomach).

Ohhhh my.

AM I THE ONLY ONE WHO SEES HOW BLATANT THIS IS?

It turns out no, I am not, and Goro himself had to deal with some suspect accusations by people who wondered if the opening murder was a playful jab (stab) at his father. He claimed that the desire to kill one’s father simply represented the desires of the “many young people” in Japan who felt oppressed by their own parents. Okay, Goro. Sure. I toootally believe you. It was for all the kids! We stan artistic expressions of national patricide.

So, yeah. Goro begins the movie by not-so-subtly killing his father. I'll get back to that. For now, more on the plot.

The reason why Arren (a marvelous little projection of Goro's psyche) kills his father is never stated. There’s some vague darkness at play that occasionally takes hold of his body and turns him into a bloodthirsty monster like some angsty Shonen Jump deuteragonist. Frustrated with how lame he is, Arren takes a sword flees and his abstract fantasy castle for some other Earthsea location. It’s there that he runs into Sparrowhawk, an old wizard guy, who rescues him from slavers, turns him away from drugs, and gives him a nice place to heal on a farm. He stays on that farm for a while, until he runs away and gets abducted by Cob, this big bad dark wizard voiced by Willem Dafoe in the English dub (lol). Cob controls Arren through his "true name," which is an important concept in the movie that is never properly unpackaged. I hope you're noticing a trend here.

As far as adaptations go, this one is a bit awkward. Goro’s Earthsea is not Earthsea as fans know it. Though the film is based on The Farthest Shore (1972), the third book in the series, Goro pulls names, characters and iconography from the first two books, splattering them carelessly throughout his movie. He ends up with a strange hodgepodge of Earthsea material lacking the essence of the original. “It is a good movie,” Le Guin told Goro after their initial screening in America, trying to be nice. She added, “it is not my book.”

It is the tonal shifts that startle the most. Don't let the pretty colours trick you: Goro's Earthsea is a remorseless world. Before Hawksparrow finds him, Arren traverses a wasteland teaming with rabid beasts. Forests and farmlands are fading away, consumed by a mysterious evil. If you think this invites some typical Ghibli environmentalism, not so: this is as decidedly un-Ghibli as you could possibly be. No Ghibli movie, as far as I’m aware, has presented to the audience systematic slavery, villains who attempt to literally rape a young girl, or a protagonist that would murder a family member for seemingly no reason.

As Le Guin wrote in her own blog (blog wars!), “[the film] was maintained by violence, to a degree that I find deeply untrue to the spirit of the books.”

This speaks to Goro’s inexperience as a storyteller. Most of the film is heavy-handed, bumbling over its themes and failing to complete them without using quick fixes like stabs and slashes. That's where his immaturity shows the most. The actual animation direction looks fine, at least to me. I’m sure Goro had a lot of help from a Ghibli team that were committed to realising his vision, no matter how problematic it could be.

But what did Hayao Miyazaki say on the matter? “You shouldn’t make a film based on your emotions." Pshht. Preachy and hypocritical. He did the same thing in Porco Rosso (1992) and The Wind Rises (2013), and they didn’t suck. But he does have a point insofar that the Earthsea series, as popular and respected as it is, shouldn’t really be your artistic sandbox to act out your latent patricidal desires. Let's get back to those!

Here's another excerpt from Goro's blog:

“Once the publicity for "Tales of Earthsea" starts up, regardless of whether I like it or not, as the director, I can easily imagine that I will be labelled with the adjective "Miyazaki Hayao's son". Faced with this, the conclusion Producer Suzuki came out with was that obviously I should "let the work itself speak for me", but "in order to showcase 'the work itself' you still need to let them know you not as 'Miyazaki Hayao's son', but as the individual human being Goro Miyazaki.”

Very insightful, Goro. You see it throughout the film—this bloodlust for identity. I go as far to call this the main theme, far more pronounced than those to do with life and immortality. Goro refutes his father's central ethos, embracing an ugly, violent protagonist and depicting the world in a state of increasing ruin. This is no Hayao Miyazaki movie. For better or worse, this is a Goro Miyazaki movie.

His neurotic urge to detach himself from his father manifests in the artwork. Le Guin was unhappy with the way the film looked, stating “the animation of this quickly made film does not have the delicate accuracy of Totoro or the powerful and splendid richness of detail of Spirited Away.” She’s right, but I'm not convinced that's because Goro was cutting corners.

In Earwig and the Witch and its TV series predecessor Ronia, the Robber's Daughter (2013), Goro employed CG animation, deciding he wanted to experiment with new animation styles instead of rehashing the tried-and-true formula. One might speculate that this is another jab at his dad, who is known for belching at anything CG.

Tales From Earthsea doesn't go quite that far, but the animation is decidedly un-Miyazaki. Apparently, it's more of a tribute to his favourite movie, which is Isao Takahata’s The Little Norse Prince (1968). Which means Goro was team Takahata all along! Take that, dad (along with the sword to the stomach!). The character designs and general style reflect this core influence. Of course, it’s understandable why Le Guin would be so pissed, seeing as she signed up for that vintage Miyazaki goodness.

To make my position clear (not that it really matters), I like the idea of moving beyond the Hayao Miyazaki mould, because obviously only one person can do that. I admire the decision to take artistic risks. I should note that there are some other cool creative decisions, including the use of these interesting classic-looking paintings for the night sky. Quite nice. Of course, no one really talks about this stuff in a positive light. Goro is reduced to Miyazaki’s son whether he likes it or not, and that means people will always smirk at these awkward, flailing innovations as the boy writhes and screams, eternally bound to his father’s shadow.

Does this horsey thing look familiar to you? It’s a lot like the horsey thing from Princess Mononoke 1997). Really, Arren has a lot in common with Ashitaka, in addition to the obvious physical resemblance. He’s a young, cursed, terribly bland prince… of all the Ghibli protagonists, Goro, why did you transplant that one?

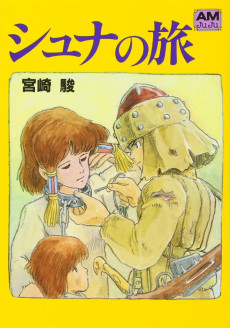

I’m bringing this up in order to condradict my previous point (perhaps this is why I never passed a high school English essay). There is a very interesting paradox here! For all Goro tries to escape Miyazaki’s shadow, he deliberately pays “homage” to his father in certain ways. The Mononoke similarities are just the first ones I noticed; Miyazaki stans of a greater calibre than I have pointed out countless recreations of classic Miyazaki scenes dating back even before the foundation of Ghibli. I’ve also discovered that the plot of this movie in some ways draws more from Miyazaki's watercolour manga The Journey of Shuna (1983) than it does from Le Guin's books.

Why would Goro do this? We've established he wants to forge his own identity as a filmmaker, and that's understandable. Why does he force himself into imitation? An act of spite, perhaps? Besmirching the Miyazaki name? Assassinating not only his person, but his work? Mayyybe. I’d love to make that argument, but I’m coming at it from a different angle.

I see this as an act of sincerity. Broadly, this film maps a conflicted relationship with the past. It's actually quite metafictional, considering its role in the Ghibli canon. We see Goro's protagonist stuck, after “killing” his father, in a hellish repetition of Miyazaki scenes, characters, and iconography. It is only after he and his dragon girlfriend call each other by their "true names" that they escape this cycle of grief, allowing Goro to ideally transcend the Miyazaki mantle.

Am I giving Goro too much credit? Because I do not think this rehash of classic Miyazaki content is an example of unoriginality or even reverence. It is not, as many have accused, an attempt to copy his father. Instead, it’s a legitimate attempt to reason with the man who "raised" him, not through physically being there, but through the films he produced. No deep dive into his familial strife would be complete without Miyazaki’s work.

But it’s not just Miyazaki! This movie is a full-frontal assault on the past. One need only look at the world around Arren to see that this film is trying to comprehend what once were esteemed structures falling into ruin. Considering Goro is a literal landscape designer, the disrepair of Earthsea’s surroundings are more relevant. When it comes to ruined buildings, at least, he probably knows what he's talking about.

And we can take this further! The past, in many ways, is embodied by the film’s villain. Cob (again, Willem Dafoe) really is a shallow, cheesy character, but they serve an interesting thematic purpose. Cob is in pursuit of immortality. When they are vanquished at the end of the movie, Arren tells them that there is no point living anymore; at some point, you have to go off and die, even if you are immensely powerful and acclaimed, obsessed with extending your wretched life.

Addressing that to someone in particular, Goro? Hehe.

Seriously, though! In lieu of those who came before and all the great things they made, the movie flails around, picks itself up, and constructs an alternate future. Arren, Therru, Sparrowhawk, and that one white girl band together and live as a family. One family destroyed, another formed. Out with the old and in with the new.

I see this trend across Goro’s filmography. Ever noticed that not a single one of his protagonists have living, present fathers? Arren promptly disposes of his. In Up From Poppy Hill (2011), Umi's died in the war. In Earwig and the Witch, Aya’s dad is not mentioned once, and her rockstar mother abandoned her as a child. Of course, this doesn’t mean they’re alone. Found families abound! Goro trivialises the past before building a new one. He takes his role as the new guard of Ghibli literally and emotionally.

We’ve established that Tales From Earthsea, interesting as it is to talk about, isn’t that good. It fails as an Earthsea adaptation and doesn't handle its themes too well.

But I want to end this review positively. About halfway through, Arren stumbles across the main girl—Therru—singing atop a grassy hill. This is going to sound cheesy, but bear with me.

Therru sings this song, and it’s just her voice. No music, no soundtrack. It goes on for quite a few minutes, too. In several interviews, Miyazaki senior harps on about "ma" (間), that Japanese word that describes a break in the action. In these scenes, the audience is allowed to breathe, relax, and, in Goro's case, properly grieve. These scenes are, to me, a marker of maturity.

Believe me when I tell you Therru's song is legitimately gorgeous! The girl stands on that grassy hill, wishing someone might understand how sad and lonely she is. Sounds melodramatic? It doesn't come off that way. The song shines a light not only on her, but also Arren. We see him shed a tear for the first time in the movie, revealing that he's not a soulless, edgy Ashitaka skin, but a traumatised boy dealing with his own demons.

I should note that the lyrics of this song were not penned by the film’s composer, Tamiya Terashima, who Goro selected because Joe Hisaishi was “too old” for them to get along (I find this funny). Instead, they were written by Goro himself. Straight from the heart! His emotions here are pure, undiluted, and beautiful.

And his expressions in this scene. If there’s one thing this movie does better than damn near any Ghibli movie I’ve seen, it’s the facial expressions. There is just so much pain bottled up in Arren’s hurt little face. A blessing of the Takahata style? Or is it Goro's secret genius? I don't know, but the faces, simple as they are, communicate so much in this film. Arren's sad default expression contrasts effectively with his twisted “mask” that belongs to his doppelganger.

After the song, Arren and Therru sit down for a heart to heart. We learn that Therru has been short-changed by her own parents (nothing says anime abuse like a burn mark), and actually seems to like Arren a lot more when he cries and confesses his patricide. From then on, the two form a strong, believable bond that gives the movie some much-needed stability.

I really love that scene. As mean as I've been, I hope I've also proven Goro is not a lost cause. He is capable of beautiful, heartfelt moments. He is capable of tossing together a feature-length film with Hayao Goddamn Miyazaki actively lobbying against him. He is capable of a lot of things, really.

I hope, like Arren, he finds his true name someday.

⬥ Here are some links to Goro Miyazaki’s journals and Ursula K Le Guin's response to the film, both of which I’ve quoted throughout. Oh, and here’s that video where Hayao Miyazaki walks out on his son’s movie. Yikes. At least he attempted to make up for things in future movies, working alongside Goro instead of sabotaging his first attempt at direction.

His parenting gets about the same score as this movie. Maybe a little lower. Thanks for reading!

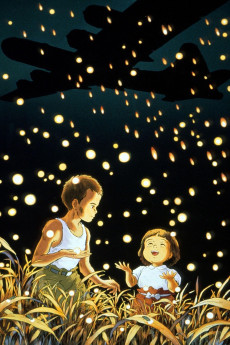

SIMILAR ANIMES YOU MAY LIKE

MOVIE AdventureTenkuu no Shiro Laputa

MOVIE AdventureTenkuu no Shiro Laputa MOVIE ActionMononoke-hime

MOVIE ActionMononoke-hime MOVIE ActionNi no Kuni

MOVIE ActionNi no Kuni MOVIE AdventureSen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi

MOVIE AdventureSen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi MOVIE DramaHotaru no Haka

MOVIE DramaHotaru no Haka MOVIE AdventureMimi wo Sumaseba

MOVIE AdventureMimi wo Sumaseba ANIME AdventureSousou no Frieren

ANIME AdventureSousou no Frieren ANIME AdventureOokami to Koushinryou

ANIME AdventureOokami to Koushinryou ANIME AdventureSomali to Mori no Kamisama

ANIME AdventureSomali to Mori no Kamisama ANIME ActionOusama Ranking

ANIME ActionOusama Ranking

SCORE

- (3.2/5)

TRAILER

MORE INFO

Ended inJuly 29, 2006

Main Studio Studio Ghibli

Trending Level 1

Favorited by 363 Users