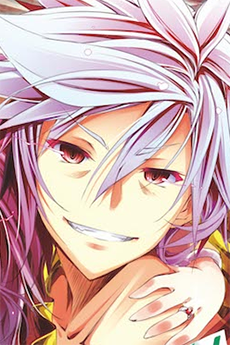

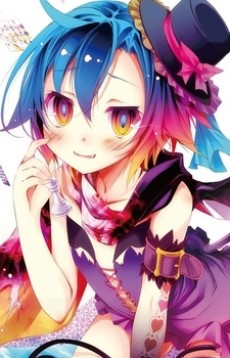

NO GAME NO LIFE

STATUS

RELEASING

VOLUMES

Not Available

RELEASE

Invalid Date

CHAPTERS

Not Available

DESCRIPTION

In this fantasy world, everything's a game--and these gamer siblings play to win! Meet Sora and Shiro, a brother and sister who are loser shut-ins by normal standards. But these siblings don't play by the rules of the "crappy game" that is average society. In the world of gaming, this genius pair reigns supreme, their invincible avatar so famous that it's the stuff of urban legend. So when a young boy calling himself God summons the siblings to a fantastic alternate world where war is forbidden and all conflicts--even those involving national borders--are decided by the outcome of games, Sora and Shiro have pretty much hit the jackpot. But they soon learn that in this world, humanity, cornered and outnumbered by other species, survives within the confines of one city. Will Sora and Shiro, two failures at life, turn out to be the saviors of mankind? Let the games begin...!

(Source: Yen Press)

CAST

Shiro

Sora

Stephanie Dola

Jibril

Schwi Dola

Riku Dola

Izuna Hatsuse

Tet

Chlammy Zell

Fiel Nilvalen

Miko

Couronna Dola

Azriel

Think Nirvalen

Plum

Nonna Zell

Horou

Einzig

Ino Hatsuse

Emir-Eins

Raphael

Mahakoht Dola

Artosh

Tilvilg Nýi

Amira

CHAPTERS

RELATED TO NO GAME NO LIFE

MANGA AdventureNo Game No Life

MANGA AdventureNo Game No Life ANIME AdventureNo Game No Life

ANIME AdventureNo Game No Life MOVIE ActionNo Game No Life Zero

MOVIE ActionNo Game No Life Zero MANGA ComedyNo Game No Life, desu!

MANGA ComedyNo Game No Life, desu!REVIEWS

KuroGFX

0/100Lost in the Infinite Loop: A Sleep-Deprived Cynic’s Frantic Ramblings on Life, Self-Help, and Video Game LogicContinue on AniListI hate the idea of locking myself into any firm stance. I’m always hedging, trying to see things from every angle, which leaves me constantly on the fence. I worry that this will leave me isolated, unable to connect fully with anyone, because I’m never willing to commit to one viewpoint. It’s not just the isolation itself that bothers me; it’s the fear of being trapped in my own mind, just me and my endless thoughts, watching as life slips by. The idea of getting old, stuck in some kind of theoretical bubble, just thinking about a world I’m not really part of—it’s unsettling. Maybe that’s why I take my health seriously and push myself to keep working on things, almost as a way of avoiding slipping back into that hikikomori mindset. Then there’s the fear that I’ll spend my whole life searching—through self-help books, fiction, or whatever—and never find a way to resolve the things that feel broken in me. I feel like I’m always trying to find a “success paradigm,” something that could help me navigate life without getting stuck in the same loops. It’s this hope that, through my own effort or the right knowledge, I’ll eventually stumble onto something I can rely on to guide me. But what if that doesn’t exist? What if I’m just fundamentally flawed—someone who will always be socially anxious, awkward in groups, never quite fitting in? It’s like, if I can’t even manage the basics, does that mean I’m not worth much in the first place? Was I just set up to fail? Sometimes, I wish there was an objective system—some kind of computer that could record all my data and find the optimal path for my life. I feel like a lot of people benefit from having a set path, like a video game with clear rules and progression. In real life, everything is too broad. People move in random directions, and there’s no clear pathway, no sense of what leads to success or failure. It’s like some messed-up open-world game where you can’t even tell if you’re losing until you’re already halfway in the mud of your own grave. That’s why No Game No Life resonates so deeply for me. It captures the insanity of a world without inherent rules—aside from physics or nature’s laws, which we barely understand and keep learning more about, only to realize how little we know. In a world with clear, defined rules, people like Sora and Shiro can thrive. They’ve “won” because, in any game, all you need is a rational understanding of the mechanics, and the confidence that those mechanics won’t betray you. In contrast, our own rules—laws, morals, all of it—are things we made up, like scaffolding we’re using to build a society that feels stable. Money, for instance, is purely an idea, something everyone agrees on even if religions or ideologies can’t agree on anything else. Even though a dollar bill has almost no intrinsic value, we’ve all decided it’s worth something because we trust the system backing it. But underneath, it’s just paper. Freedom with limitations is what makes games engaging. The prisoner’s dilemma shows us how rules encourage ingenuity, the curiosity to experiment with what’s allowed. Personally, I find open-world games overwhelming. They give you so much freedom that it actually kills the desire to explore—too many options, too little guidance. So what do I do? I end up locking myself in my room, maybe a little numb from the endless internet content, and I try to find answers in books, articles, whatever I can. Not because I’m obsessed with health or self-improvement, but because I’m trying to find my playstyle for this life—a life where every option imaginable is laid out, yet without any clear route to take. And with every choice, the fear is that if I mess up my build, I’ll have to start from scratch, all over again. Sora and Shiro’s victories in No Game No Life are built on the idea that Disboard operates on strict rules and enforced peace through game-based conflict resolution, but the world has become stagnant. Their opponents play in an environment where geopolitical warfare and interpersonal rivalries are contained within passive-aggressive, risk-averse games. As a result, Disboard’s world lacks the pressure that pushes people to innovate out of necessity—a pressure that’s driven our world to advances in warfare, medicine, art, and technology, especially in the last century. Sora and Shiro come from a reality defined by inconsistency, strife, and a constant need to adapt or risk falling behind. They’ve experienced a world where conflict forces growth, where understanding the unknown and constantly innovating are matters of survival. This chaotic background has armed them with hard-earned knowledge that proves invaluable in Disboard—a world that hasn’t been pressured to learn or innovate. When Sora and Shiro face opponents like Jibril, their advantage is clear: they draw from a well of knowledge that includes nuanced understandings of science, language, and strategy, concepts Jibril can’t fully grasp. For instance, Jibril’s ignorance of terms like "Core" or "Mantle" in their game ultimately seals her defeat. They thrive in Disboard not because they are simply better players, but because they’ve been tempered zy a world where knowledge is fragmented and rapidly evolving, where each new insight or strategy could mean the difference between success and failure. In the end, Sora and Shiro exploit this complacency in Disboard’s inhabitants. They are players from a reality where nothing is guaranteed, where survival is achieved by those willing to outwit or outlast constant changes. Their skill isn’t about escaping reality’s rules but about mastering them, taking advantage of their opponents’ comfort with stability and static rules. This is perhaps what makes them so captivating to watch: they aren’t just winning a game; they’re bringing the ingenuity, struggle, and restless creativity of humanity into a world that has forgotten these things. Sora and Shiro are escapist losers. They couldn’t make it in their own world, and only by being placed in an environment perfectly suited to their skills and knowledge are they able to thrive. Their flaws—rooted in their lives as NEETs, hikikomori, and outcast otaku—still linger. Despite their success in Disboard, the trauma and stigma of their past remain. They didn’t really overcome their problems. This is something the light novels try to address later on. One of my issues with the isekai genre is that while it's often framed as escapism, being transported to another world doesn’t solve your underlying flaws. Even in an ideal world, as long as people are still people, their issues will follow them. It doesn’t matter where you go—your problems won’t vanish just because a god transports you to some perfect reality. The same can be said for Momonga in Overlord. When he becomes Ainz Ooal Gown in Yggdrasil, the NPCs and the guild itself become real, but does he find happiness in that? No. Instead, he feels the erosion of his own identity. He clings to the memories of the friends he once had in the game, but that hope has turned into an obsession that consumes him. He is no longer Suzuki Satoru or even Momonga, the player—he becomes the guild itself, the very thing he worked tirelessly to preserve. His entire identity is consumed by the role he played in Overlord, becoming a literal embodiment of Ainz Ooal Gown. This happens to other isekai protagonists too, including Sora and Shiro. While they’re succeeding in Disboard’s reality, eventually, their human weaknesses will resurface. Success in an ideal world doesn’t erase the underlying struggles or flaws that they carry with them. Just like Momonga, their escapism will eventually collide with the same issues they tried to run away from.

SIMILAR MANGAS YOU MAY LIKE

NOVEL ActionSword Art Online

NOVEL ActionSword Art Online NOVEL ActionMasou Gakuen HxH

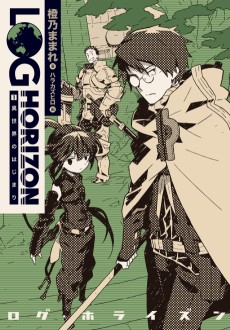

NOVEL ActionMasou Gakuen HxH NOVEL ActionLog Horizon

NOVEL ActionLog Horizon

SCORE

- (4.05/5)

MORE INFO

Favorited by 703 Users